Genetic analysis aids classification, therapeutic decisions

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

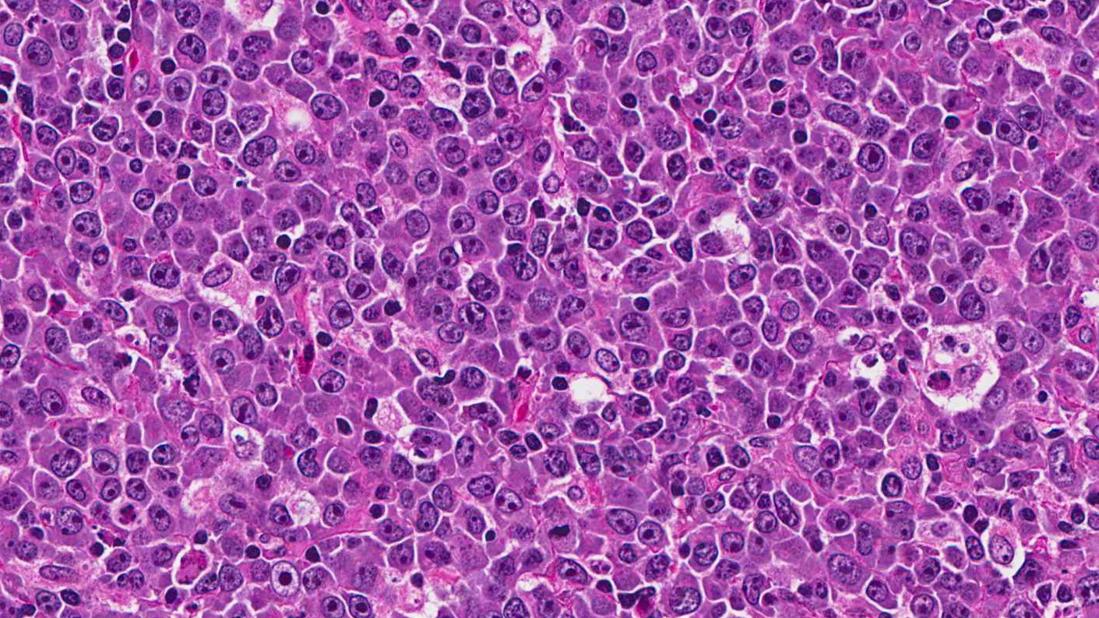

Lymphomas are among the more difficult malignancies to understand, with a complex classification system.

Until recently, from a clinical standpoint I was a “lumper,” simply considering a lymphoma as indolent or aggressive. Now we must all become “splitters,” as enhanced understanding of the molecular genetic pathophysiology of various lymphoma subtypes impacts prognosis and treatment.

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common lymphoma subtype and the prototype for aggressive lymphomas, is now recognized as a family of diseases with different genetic drivers. Most DLBCLs are categorized as either germinal center (GC) cell or activated B cell (ABC) subtypes.

The good news is that we continue to cure a high percentage of DLBCL patients with the standard chemotherapy combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R–CHOP).

The not-so-good news is that the ABC subtype has a poorer prognosis than does GC. Accurate characterization of the ABC or GC subtype relies on gene expression analysis that has not been routinely available. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is an available but imperfect surrogate.

Our Cleveland Clinic pathology colleagues have developed a polymerase chain reaction-based multigene assay that we now routinely utilize to assign subtype when making new diagnoses of DLBCL.

A nonoverlapping prognostic categorization depends on MYC and BCL2, either at the gene rearrangement or protein expression level. Both genes

are chromosomally translocated (usually t(8;14) for MYC and t(14;18) for BCL2) in the relatively uncommon (~5 percent) “double-hit” DLBCL. Double-hit DLBCL patients have poor outcomes with R-CHOP, and we usually treat them instead with the dose-adjusted regimen of etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R).

Advertisement

More common are “dual-expressors” — DLBCL patients who are IHC-positive for both MYC and BCL2, but without translocations. Though outcomes for these patients are not optimal, R-CHOP remains the standard treatment. Novel research approaches are in development.

Does ABC versus GC subtype affect treatment? Not yet, but soon. ABC-DLBCL is driven by the NF-kB pathway, a prime target of proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib. Several randomized studies comparing R-CHOP with or without bortezomib in DLBCL have been completed, with more results expected soon.

One issue is excess neuropathy due to the combination of bortezomib with vincristine. Cleveland Clinic is conducting a phase 1 and 2 trial of initial DLBCL therapy combining R-CHOP with the nonneurotoxic proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib (an approved drug for myeloma). The current dose-finding cohort permits all DLBCL subtypes, while the expansion cohort will focus on the ABC subtype. The GC subtypes do quite well with current therapy, but look for trials combining epigenetic or BCL2-inhibiting agents with R-CHOP for these patients, based on biological insights gained from gene expression and genetic analyses.

Despite generally favorable outcomes for DLBCL, as many as 30 to 40 percent of patients relapse and require additional therapy. In fact, as fewer patients relapse after initial therapy, outcomes for those who do relapse are worse.

There is no standard therapy for patients who relapse after, or who cannot undergo, dose-intense chemotherapy with stem cell support. We are investigating novel approaches for such patients.

Advertisement

Patients whose DLBCL carries a mutation in the MYD88 gene (commonly altered in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia) — which can be tested in previously biopsied tissue even before the patient requires therapy — are eligible for a dose-finding study of IMO8400. This oligonucleotide, administered subcutaneously twice weekly, blocks Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling through MYD88.

For the majority of patients without MYD88 mutation, we offer selinexor, a first-in-class selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) that binds to the nuclear pore to prevent passage of growth regulatory proteins into the cytoplasm, inducing cytotoxicity. It is attractive mechanistically and because it is an oral agent.

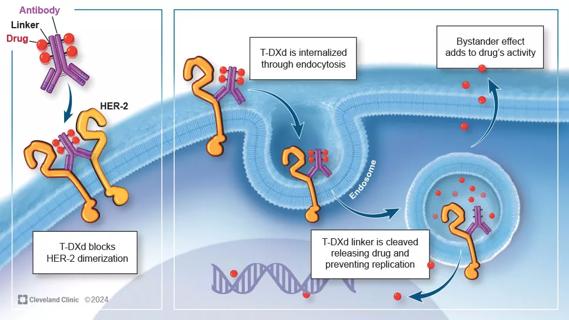

Cleveland Clinic is about to open three additional studies of novel agents. One study uses an antibody to PD1 (which is well-known from recent approvals in melanoma and lung cancer as a means to restimulate T cells to attack cancer) to treat patients with relapsed DLBCL. The other two use antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which target a cytotoxic drug directly to cells expressing the target of the antibody. This strategy has been highly effective against CD30-expressing lymphomas. These two ADCs each target a different antigen — either CD19 or CD37 — expressed almost exclusively on the surface of some normal B cells and almost all B cell lymphomas.

Stimulating the immune system to kill malignant cells has been a long-sought goal that is only recently showing broadly applicable efficacy. Antibody interference with PD1/PDL1 interaction to re-energize existing tumor-specific T cells is one exciting approach. Bispecific antibodies such as the anti-CD19-CD3 antibody blinatumomab harness nonspecific T cells to bind to CD19-expressing lymphoma/leukemia cells.

Advertisement

Another approach is to insert a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) into T cells (CAR-T) so that, when re-infused, they will be activated upon binding to the tumor cell. The CAR-T cells currently in use for lymphoma have a single transmembrane protein in which the external domain binds to CD19 and the internal domain contains T cell activating and coactivating domains.

Logistically, a patient undergoes a single leukapheresis to collect T cells, which are then engineered into CAR-T, a process that takes 7 to 10 days in the lab. Meanwhile, the patient undergoes relatively mild lympho-depleting chemotherapy, followed by CAR-T re-infusion. The main toxicity is often an acute, transient cytokine release syndrome that occurs about one week post-infusion.

Cleveland Clinic is conducting a clinical trial of CAR-T cell therapy in patients with relapsed DLBCL.

In conclusion, standard cytotoxic chemotherapy combinations (R-CHOP front-line and high-dose at relapse) are effective and will remain important components of therapy for DLBCL. Targeted approaches are moving quickly into the clinic, however, including agents targeting intracellular processes, surface molecules and the immune system.

Dr. Smith is the Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Lymphoid Malignancy Program and a staff member of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology.

Advertisement

Advertisement

First-of-its-kind research investigates the viability of standard screening to reduce the burden of late-stage cancer diagnoses

Global R&D efforts expanding first-line and relapse therapy options for patients

Study demonstrates ability to reduce patients’ reliance on phlebotomies to stabilize hematocrit levels

A case study on the value of access to novel therapies through clinical trials

Findings highlight an association between obesity and an increased incidence of moderate-severe disease

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Institute takes multi-faceted approach to increasing clinical trial access 23456

Key learnings from DESTINY trials

Overall survival in patients treated since 2008 is nearly 20% higher than in earlier patients