Lesion pattern easily identifiable on colonoscopy

The colorectal cancer predisposition syndrome called MYH-associated polyposis (MAP) is a diagnostic challenge. Resulting from mutations in a gene that’s critical to base excision DNA repair, MAP overlaps clinically with mild familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and other hereditary colon cancer syndromes. Because MAP is recessively inherited, the affected individual may have no family history to tip off the clinician to its presence.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“MAP is a great mimic of other syndromes. It can look like FAP, sporadic colon cancer, young age of onset of colon cancer, Lynch syndrome, or familial colon cancer type X, so it’s probably under-recognized,” says James Church, MD, Director of the Sanford R. Weiss, MD, Center for Hereditary Colorectal Neoplasia at Cleveland Clinic.

But identifying MAP, which Dr. Church likens to “a very mild dose of FAP,” is important because its clinical course is often relatively mild and colectomy may not be necessary. In addition, “MAP is recessive and FAP is dominant. That makes a difference to familial risk, genetic testing strategy and other organ involvement.”

Until now, there has been no specific clinical sign that a person has MAP. But Dr. Church and his colleague Sara Kravochuck, RN, have found one that’s easily identified on colonoscopy: A rectum that is “studded” with small, flat, pale, very dense hyperplastic polyps in the low rectal mucosa. The presence of this distinct lesion pattern should trigger a referral for genetic testing, he says.

“Hyperplastic polyps are common in the rectum, but this is just a unique appearance in the very low rectum, with lots of these tiny ‘bubbles’,” Dr. Church explains.

Their study, published in the June 2016 issue of Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, involved 49 patients referred for endoscopic surveillance and polyp control, including 16 with biallelic germline MYH mutations. Rectal studding was present in 10 of those 16 but not in any of the other patients, whose diagnoses included FAP, serrated or mixed polyposis, and PTEN mutation.

Advertisement

“In my experience, rectal studding is unique to MAP,” Dr. Church says.

Rectal studding differs visibly from the more common rectal clustering of hyperplastic polyps in several ways: Studding typically includes more than 50 hyperplastic polyps, whereas rectal clustering involves much fewer. Lesion density is far greater with studding, sometimes to the point of confluence.

Lesion size is also smaller with studding — about 1 to 2mm versus less than 1cm for clustering. In contrast to the typically oval clustered lesions, rectal studding lesion shape is more variable but often circular.

“The distinction is hard to describe but obvious on endoscopy,” Dr. Church and Kravochuck write.

Discovered in 2003, MAP is believed to account for less than half of one percent of all colorectal cancers. But, Dr. Church says, “It could be more. This is still a relatively new syndrome, and a lot of doctors have never heard of it.”

Because the MYH mutations can affect tumor suppressor genes, the syndrome predisposes patients to cancers of the stomach, small intestine, and thyroid as well as the colon and rectum.

But on the positive side, the range of cancer types and the overall risk for cancer in MAP is lower than for FAP, so that some MAP patients may not need to have their colons removed as is standard treatment for FAP.

Instead, MAP patients can be placed under more intensive surveillance for the related cancers, and family members are tested as well. For affected patients, colonoscopies should be done at least biannually but not necessary annually as is recommended for FAP patients, Dr. Church notes.

Advertisement

Patients with MAP should be referred to a center that specializes in hereditary colon cancers. There are at least 18 currently in the U.S., with Cleveland Clinic’s Weiss Center having one of the largest registries and the greatest experiences in terms of number of patients, endoscopies and surgeries performed.

Dr. Church himself currently follows about 15 MAP patients, all of whom sought him out because they wanted to keep their colons. “I follow them every year with colonoscopy, and remove polyps that look suspicious. I try to safeguard them against getting cancer.”

So what causes this “studded” lesion pattern? It’s not clear, but Dr. Church says it’s something unique to the lower rectum. “This doesn’t happen in the colon or upper or mid-rectum. There’s probably something about the cellular environment or genetic metabolism that makes it susceptible to these mutations.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

First-of-its-kind research investigates the viability of standard screening to reduce the burden of late-stage cancer diagnoses

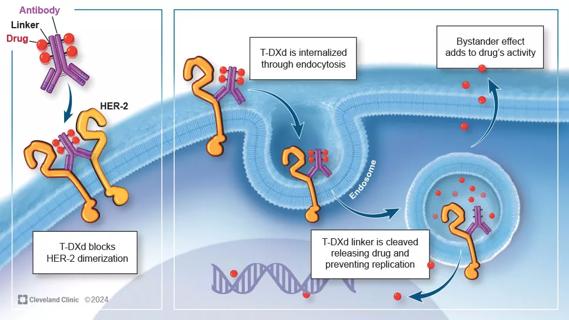

Global R&D efforts expanding first-line and relapse therapy options for patients

Study demonstrates ability to reduce patients’ reliance on phlebotomies to stabilize hematocrit levels

A case study on the value of access to novel therapies through clinical trials

Findings highlight an association between obesity and an increased incidence of moderate-severe disease

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Institute takes multi-faceted approach to increasing clinical trial access 23456

Key learnings from DESTINY trials

Overall survival in patients treated since 2008 is nearly 20% higher than in earlier patients