Screening tool given at check-in, results go to EMR

By Beth Gardini Dixon, PsyD, and Isabel Schuermeyer, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is a significant stressor for even the most resilient individuals. Factors such as disease severity, complex treatment regimens and uncertainty about prognosis can magnify distress for patients and their families.

Research has demonstrated that a cancer diagnosis increases the risk for depression, anxiety and reduced quality of life. Not only are these risks present during active oncology treatment, but emerging literature on survivorship suggests that distress may persist beyond the period of active care. New standards in oncology prioritize emotional well-being as a key aspect of treatment, and Cleveland Clinic’s Taussig Cancer Institute, in collaboration with the Center for Behavioral Health, is responding with innovative screening strategies.

The prevalence of depression is markedly higher in the oncology population, at 25 percent, compared with the general population, where lifetime prevalence is 16 percent. Rates of anxiety are notably higher as well, particularly in patients with advanced cancer. These psychiatric disorders directly impact medical care and may result in prolonged hospitalizations, delays in starting treatment, reduced adherence to therapy, lower pain tolerance and a tendency to receive more aggressive therapies at the end of life. Moreover, individuals with cancer are three times more likely to commit suicide than the general population, with poor cancer prognosis conferring greater risk.

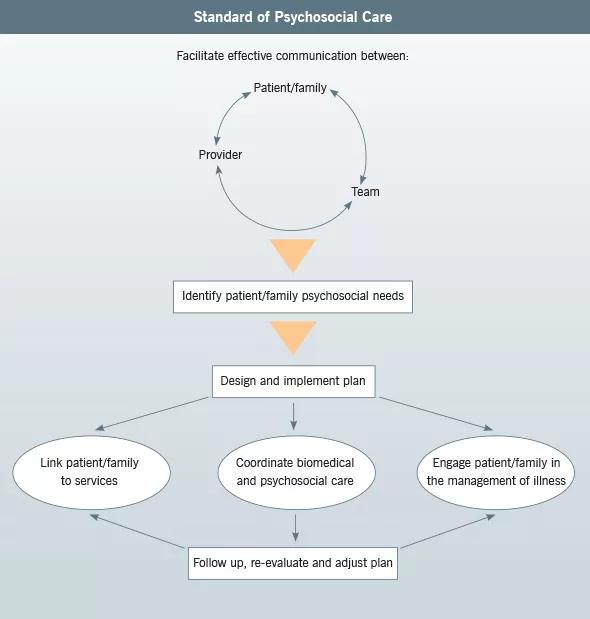

Recognizing the significant mental health needs of oncology patients, the National Institutes of Health and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) assembled a multidisciplinary committee to investigate barriers to psychosocial healthcare in ambulatory oncology centers. The committee’s findings were published in a 2007 IOM report, Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Needs,1 which outlined a new standard that integrates psychosocial health services into cancer care. Part of this new standard calls for routine psychosocial “distress” screening of oncology patients (Figure 1). The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer has adopted the IOM recommendations, adding evaluation of distress as a requisite for accreditation effective in 2015.

Advertisement

FIGURE 1.Model for psychosocial services in oncology. Adapted from the Institute of Medicine. (see Reference 1)

Some studies suggest that patients tend not to disclose their psychological concerns to their medical providers and that depression and anxiety are underrecognized and undertreated in oncology settings. Systematic screening, however, encourages early identification of and intervention for at-risk individuals, offering the opportunity to mitigate the emotional burden and medical care-related costs resulting from mental health problems.

Challenges to the implementation of screening include enabling easy completion by patients and delivering clinically relevant results to providers in a rapid, accessible manner. As more healthcare systems incorporate electronic medical records (EMRs), integrating screening data into the chart is critical.

Our psychosocial oncology program has developed a screening system that uses a unique Cleveland Cleveland-designed tool called the Knowledge Program. The Knowledge Program immediately imports screening results into the EMR. Patients complete the screening tool on a tablet computer when checking in for appointments. Screening information is then transferred electronically into the EMR so that the provider has the results prior to seeing the patient. This system allows for intervention during the appointment and helps guide referrals to specific services.

Another distinctive feature of the Knowledge Program-based screening method involves compilation of results into a database for analysis. Data may be sorted according to multiple variables, such as demographics, disease type and test scores. Comparing aggregate data to expected patterns based on the published literature has enabled us to gauge whether we are meeting the program goals.

Advertisement

During our pilot phase of screening implementation, this data analysis capability highlighted limitations of the trial screening instrument we were using, which appeared to underestimate clinically significant distress levels in our outpatient oncology population. For instance, this instrument found only 9 percent of patients in the first quarter of 2013 to have moderate or high levels of distress, which is markedly lower than the expected rate of approximately 35 percent. These findings prompted us to revise our selection of screening instruments.

Psychosocial healthcare needs to be addressed throughout the continuum of cancer care. Systematically monitoring and tracking distress ‒ as one element of a comprehensive psychosocial health services program ‒ serves to uphold new quality standards in oncology and facilitate optimal treatment outcomes.

Dr. Dixon is a staff clinical psychologist in the Psycho-Oncology Program in Cleveland Clinic’s Taussig Cancer Institute.

Dr. Schuermeyer is Director of Psycho-Oncology and a staff psychiatrist in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Behavioral Health and the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology.

Advertisement

Advertisement

First-of-its-kind research investigates the viability of standard screening to reduce the burden of late-stage cancer diagnoses

Global R&D efforts expanding first-line and relapse therapy options for patients

Study demonstrates ability to reduce patients’ reliance on phlebotomies to stabilize hematocrit levels

A case study on the value of access to novel therapies through clinical trials

Findings highlight an association between obesity and an increased incidence of moderate-severe disease

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Institute takes multi-faceted approach to increasing clinical trial access 23456

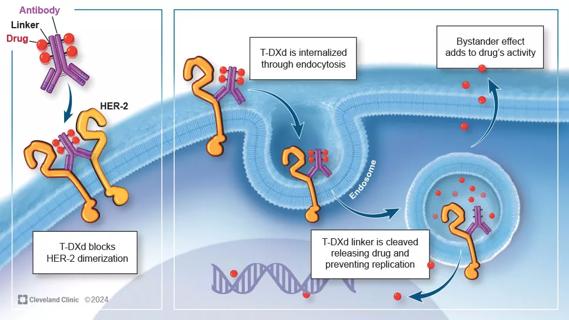

Key learnings from DESTINY trials

Overall survival in patients treated since 2008 is nearly 20% higher than in earlier patients