By Mikkael Sekeres, MD, MS

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

I had to admit I was more than a little excited to see my next patient. This was a big day, for both of us.

Five years earlier, when he was 68, he had come to the emergency room, feeling terrible. His white blood cell count was higher than his age, and he was profoundly anemic — really, to a degree that was almost incompatible with life. He was transferred to our hospital, where we performed a bone marrow biopsy that clinched the diagnosis of acute leukemia.

Our definition of “cure” is a functional one. I can’t look a patient in the eye and tell him right after a round of chemotherapy that I was able to remove all of the cancer, as a surgeon might after an operation to excise a tumor. “Cure,” for us, means a person has lived five years without the leukemia coming back.

For my patient, that meant this day.

Read the full New York Times column by Dr. Sekeres.

Advertisement

Advertisement

First-of-its-kind research investigates the viability of standard screening to reduce the burden of late-stage cancer diagnoses

Global R&D efforts expanding first-line and relapse therapy options for patients

Study demonstrates ability to reduce patients’ reliance on phlebotomies to stabilize hematocrit levels

A case study on the value of access to novel therapies through clinical trials

Findings highlight an association between obesity and an increased incidence of moderate-severe disease

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Institute takes multi-faceted approach to increasing clinical trial access 23456

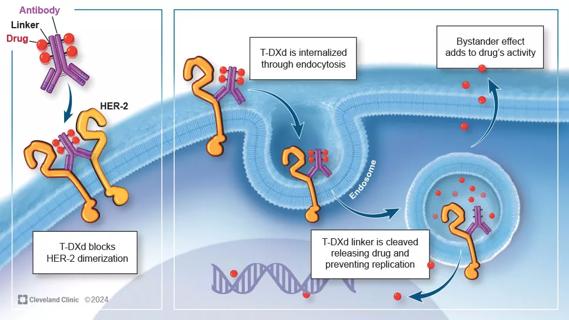

Key learnings from DESTINY trials

Overall survival in patients treated since 2008 is nearly 20% higher than in earlier patients