How easy access to 3,100 skeletons has refined our surgical techniques

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/90f5f272-1ddd-4a4c-ba78-c118b1772669/Hamann-Todd-Collection-Hero-Image-690x380pxl_jpg)

Hamann-Todd-Collection-Hero-Image-690x380pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Less than a mile from Cleveland Clinic’s main campus, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History houses the Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection, which includes the largest documented collection of human skeletal remains in the Western Hemisphere, with complete demographic information on most of its specimens. With more than 3,100 skeletons dating back to the early 20th century, the collection draws over 200 biomedical and other researchers a year from around the world.

My colleagues and I have taken full advantage of having this physical anthropology lab in Cleveland Clinic’s backyard. With free access to the collection for nonproprietary research, we’re learning from the dead to improve orthopaedic surgery techniques for the living — specifically as they relate to sports medicine. We’ve logged hundreds of hours poring over specimens, measuring three-dimensional (3-D) planes, assessing ridges and bony changes, and connecting that information to patient characteristics such as gender and age.

Although information gleaned from the Hamann-Todd Collection has advanced orthopaedic surgery around the world and expanded insights into human origins and evolution, the collection has humble origins that relied in part on the morgues and jailhouses of early 20th-century Cleveland.

The collection was started in the 1890s as an assemblage of instructional aids by Carl August Hamann, an anatomy professor at Cleveland’s Western Reserve University Medical School. Hamann grew the collection to about 100 skeletons before becoming the school’s dean in the early 1900s, handing off collection’s curation to a young Englishman, T. Wingate Todd.

Advertisement

Todd soon dramatically expanded the collection, helping write anatomical laws requiring local hospitals, funeral homes and sanitoriums to provide unclaimed corpses to the medical school. He and colleagues took measurements and photographs and meticulously catalogued as much information as possible about the specimens.

After Hamann and Todd died in the 1930s, the bones sat unused for a couple of decades before being transferred to The Cleveland Museum of Natural History from the 1950s to the 1970s. There, museum curators gave the collection new life, cleaning the bones of soot from being stored in coal bins at the medical school. They also computerized the detailed demographic information on the specimens, making the collection even more valuable and accessible for researchers.

Experts believe it is unlikely another skeleton collection of this size (over 3,100 human specimens plus skeletons of about 900 apes and monkeys), with this level of demographic detail, will ever be assembled again, as the time and expense required would be prohibitive.

The Hamann-Todd Collection offers a number of advantages over other research resources or approaches in orthopaedics, including:

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f7260a9a-a9bb-45e7-af6d-414eca2d676a/Hamann-Todd-Collection-Inset-02-590pxl-width_jpg)

Figure 1. Dr. Farrow points out the lateral intercondylar ridge on a right femur from the Hamann-Todd Collection. This landmark is used to identify the ACL footprint on the femur.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f33c1aa7-24aa-42ef-9f9d-db9e71fb3274/Hamann-Todd-Collection-Inset-03-590pxl-width_jpg)

Figure 2. Digital calipers (shown here) are among the tools available at the museum for performing measurements on skeletal specimens from the collection.

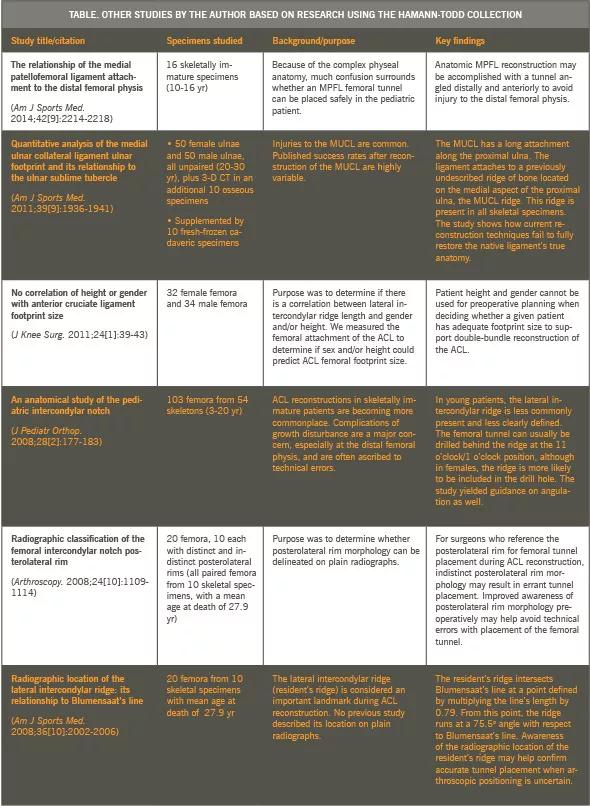

My colleagues and I have completed seven orthopaedic/sports medicine-focused studies using specimens from the collection, and we currently have another underway. Six of these studies are profiled in the table below; the remaining study, which focused on anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, has had the widest applicability and is reviewed below as a case study in how the collection facilitates our research efforts.

The ACL study, which I published as a resident in 2007, focused on the importance of proper femoral tunnel placement and sought to characterize the osseous anatomy of the femoral intercondylar notch. We studied the morphology of the notch in 200 human femora from the Hamann-Todd Collection from skeletally mature donors (age 30 or younger at death), paying specific attention to the morphology of the ridge on the lateral wall and posterolateral rim of the intercondylar notch (Figure 1).

We found that the morphology of the femoral intercondylar notch varies little. This improved knowledge of the notch morphology may assist surgeons in placing the femoral tunnel in the proper location when performing ACL reconstruction.

Prior to this study, some confusion may have existed about where the ACL should go arthroscopically. Access to a wide variety of subjects in the Hamann-Todd Collection allowed us to verify that this ridge is present in most people and can be used as a reliable landmark in ACL reconstruction. Previously, some surgeons may have mistaken the ridge for the back of the notch and consequently placed the graft in front of the footprint, resulting in poorly placed grafts.

Advertisement

My colleagues and I have been spending time with the Hamann-Todd Collection in recent months, with a study underway looking at rotator cuff impingement as it relates to some of the bony anatomy of the shoulder. When that study is completed, we will have likely exhausted our use of the collection as it relates to sports medicine surgery. However, there is still more the dead can tell us when it comes to other orthopaedic surgery applications, and additional subspecialty areas will be next on our research horizon.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/df9796ed-83f3-4041-bf3a-291e8d75795a/Hamann-Todd-Collection-Inset-Table-590pxl-width_jpg)

Dr. Farrow is an orthopaedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine in the Cleveland Clinic Center for Sports Health, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Biologic approaches, growing implants and more

Study reports zero infections in nearly 300 patients

How to diagnose and treat crystalline arthropathy after knee replacement

Study finds that fracture and infection are rare

Center will coordinate, interpret and archive imaging data for all multicenter trials conducted by the foundation’s Osteoarthritis Clinical Trial Network

Reduced narcotic use is the latest on the list of robotic surgery advantages

Cleveland Clinic specialists offer annual refresher on upper extremity fundamentals

Cleveland Clinic orthopaedic surgeons share their best tips, most challenging cases and biggest misperceptions