Research clearly shows that other factors impact most patients’ cholesterol levels

For decades, physicians have been advising their patients to restrict their intake of high-cholesterol foods to avoid cardiovascular disease. But new federal dietary guidelines now under consideration will drop the current recommendations that limit these foods.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Acknowledging decades of research that shows dietary cholesterol has little or no effect on most people’s blood cholesterol levels, the nation’s top nutrition panel said in a report released in February that cholesterol no longer should be considered a “nutrient of concern.”

The report by the panel, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), will be sent to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which publish the Dietary Guidelines for Americans every five years, including this year. The agencies typically follow the panel’s recommendations.

“The 2015 DGAC will not bring forward this recommendation because available evidence shows no appreciable relationship between consumption of dietary cholesterol and serum cholesterol,” the panel’s report says. “Cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.”

The panel does say, however, that people with certain health problems, such as diabetes, should continue to restrict intake of cholesterol-rich foods.

Cholesterol has been a fixture in dietary warnings in the United States at least since 1961, when restrictions appeared in guidelines developed by the American Heart Association (AHA) and later was adopted by the federal government.

However, in recent years, major health groups such as the AHA and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) have backed away from advocating for dietary cholesterol restrictions.

Current guidelines call for restricting cholesterol intake to 300 milligrams daily. U.S. adult men on average ingest about 340 milligrams of cholesterol a day, according to federal figures.

Advertisement

Research clearly demonstrates that other factors, including genetics—not diet—are the driving force behind cholesterol levels, says cardiologist Steven Nissen, MD, Chairman of Cardiovascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

The body generates cholesterol in amounts much larger than possible through dietary consumption, Dr. Nissen says. As a result, restricted intake of high-cholesterol foods has a negligible effect on blood cholesterol levels.

“About 85 percent of the cholesterol in the circulation is manufactured by the body in the liver,” Dr. Nissen says. “It isn’t coming directly from the cholesterol that you eat.”

When patients ask about cholesterol or seek advice on what foods to avoid, physicians should consider telling patients to avoid foods that are high in trans fats.

A simple way to help patients remember is to tell them that trans fat often appears on food labels as hydrogenated oils or partially hydrogenated vegetable oil, Dr. Nissen says.

“Those types of fats do tend to raise cholesterol and do tend to increase the risk of heart disease,” Dr. Nissen says.

One diet the panel recommended is a Mediterranean-style diet – or a diet that provides about 30 percent to 35 percent of its calories from good fat.

“We now can tell patients that a reasonable intake of eggs is all right,” Dr. Nissen adds. “That represents a big change in thinking for many.”

The new U.S. Dietary Guidelines are expected to be announced later this year.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

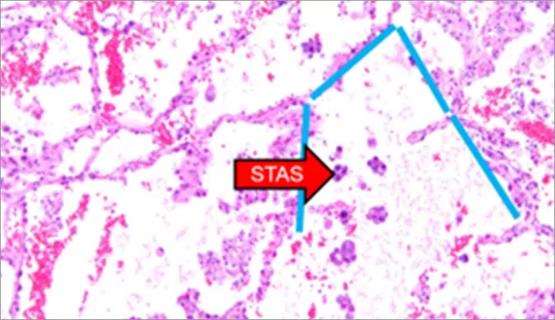

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

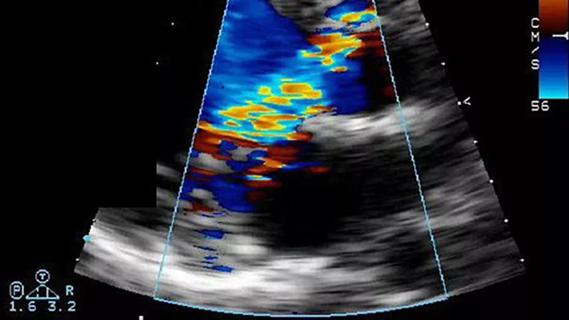

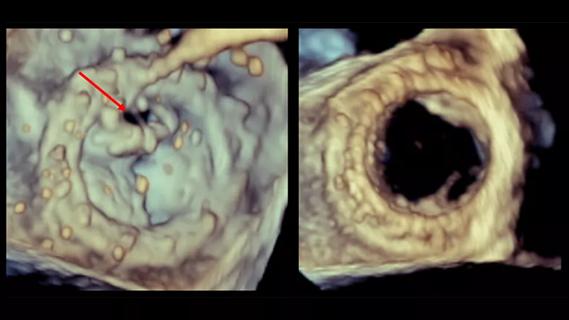

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable