Further acute testing not needed if ECG and high-sensitivity troponin are negative

Chest pain accounts for more than 6.5 million emergency department (ED) visits and 4 million outpatient visits yearly in the United States. Although half these cases prove to be noncardiac in origin, identifying patients at high or intermediate risk is a priority.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Equally compelling is the need to identify low-risk patients, who may be safely discharged without additional testing.

To help practitioners properly balance these priorities, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recently spearheaded development of a multisociety guideline for the evaluation and risk stratification of patients with chest pain.

The product of 4.5 years of work, the clinical practice guideline includes patient-centric algorithms for evaluating individuals with acute chest pain of ischemic, nonischemic and noncardiac causes, as well as those with and without obstructive coronary artery disease presenting with stable chest pain. Jointly published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation, the guideline is presented in a simplified graphic format for easy viewing on a smartphone or tablet.

“We want physicians in the acute setting to understand best practices for dealing with chest pain and be able to implement them,” says Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Wael Jaber, MD, who served on the ACC/AHA writing committee. “Providers who use this document’s evidence-based algorithms will no longer feel the need to throw every test they have at these patients.”

The guideline is endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in addition to the ACC and AHA.

Advertisement

The writing group started by expanding the definition of chest pain to include all of the following as “anginal equivalents”: pain, pressure, tightness or discomfort in the chest, shoulders, arms, neck, back, upper abdomen or jaw, as well as shortness of breath and fatigue.

They also suggested using “noncardiac” or “possibly cardiac” rather than “atypical” as a descriptor when patients do not experience the classic, gripping chest pain associated with myocardial ischemia. “The term ‘atypical’ can seem dismissive of symptoms,” Dr. Jabel explains.

An initial assessment of chest pain is recommended to determine the likelihood that symptoms may be attributed to myocardial ischemia. Because patients describe their pain using a variety of terms, a graphic was used to illustrate the likelihood these terms are associated with ischemia.

The authors advise performing an immediate, focused cardiovascular examination using signs and symptoms to identify potentially serious causes of chest pain. An ECG and a high-sensitivity troponin test should be conducted within 10 minutes of presentation to classify patient risk as low, intermediate or high.

“If these tests are negative, the likelihood of myocardial infarction is very low, and the patient may be discharged right away,” Dr. Jaber says. “It’s not necessary to keep these low-risk patients waiting for hours or days in the ED for an imaging test that is likely to increase costs without adding useful information. In these low-risk patients, deferred testing, if needed outside the acute setting, is recommended.”

Advertisement

For patients deemed to be at intermediate risk, the guideline recommends a range of noninvasive anatomic and stress testing options, including coronary CT angiography. Dr. Jaber says choice among options should be driven by the modalities available at one’s institution and by whether chest pain is acute or stable and whether the patient has known coronary artery disease.

For high-risk patients suspected of having acute coronary syndrome, invasive coronary angiography is recommended.

The document stops short of making recommendations for revascularization, as guidelines specific to that are forthcoming.

The guideline underscores the value of sharing information, treatment recommendations and options with clinically stable patients.

“It’s important to have a dialogue with patients, as it preserves their independence and autonomy,” Dr. Jaber notes. “No test is perfect, and some are not appropriate for certain individuals. Patients should know how the guideline recommendations have been reached.”

Shared decision-making between patient and clinician is also valuable when follow-up care is advised. “We want patients to understand that a negative stress test does not mean they don’t have cardiovascular disease, and that they should not stop taking their medications,” he says.

The guideline also provides advice for primary care physicians and cardiologists who have a patient presenting to their office with chest pain: Call 911 and send them to the ED, where they will receive optimal care. “Do not try to treat chest pain in a nonacute setting,” Dr. Jaber says. “You will only delay the necessary care. By the time the patient’s test results are back, a heart attack will be over.”

Advertisement

Dr. Jaber notes that for Cleveland Clinic, the new guideline is practice-affirming rather than practice-changing. Yet while the document reflects state-of-the-art knowledge, lingering evidence gaps prevent it from being the final word for every patient who presents with chest pain.

“The new guideline is excellent for detection and treatment of myocardial infarction, but developing useful guidance on pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection and other causes of chest pain and related management will require more information and more work,” says Cleveland Clinic Cardiovascular Medicine Chair Samir Kapadia, MD, who was not involved in developing the document.

Cleveland Clinic hopes to contribute to the knowledge base by determining the incremental value of positron emission tomography and investigating whether stress imaging can help shape clinical prognoses.

The writing committee identified other areas where more research is needed:

Advertisement

“We are issuing a call to arms with the hope that researchers will help fill these knowledge gaps,” Dr. Jaber concludes.

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

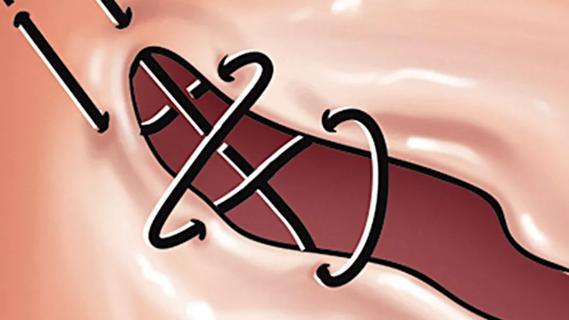

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

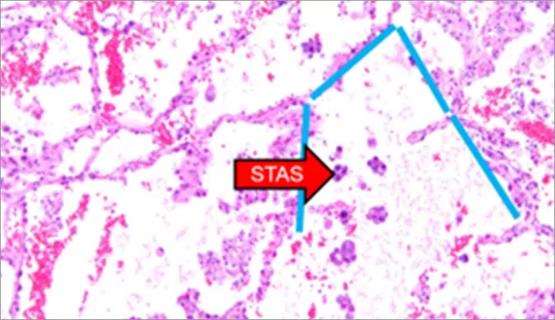

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable