Its lethality demands comprehensive experience and tools

By Gösta B. Pettersson, MD, PhD; Brian Griffin, MD; Steven M. Gordon, MD; and Eugene H. Blackstone, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

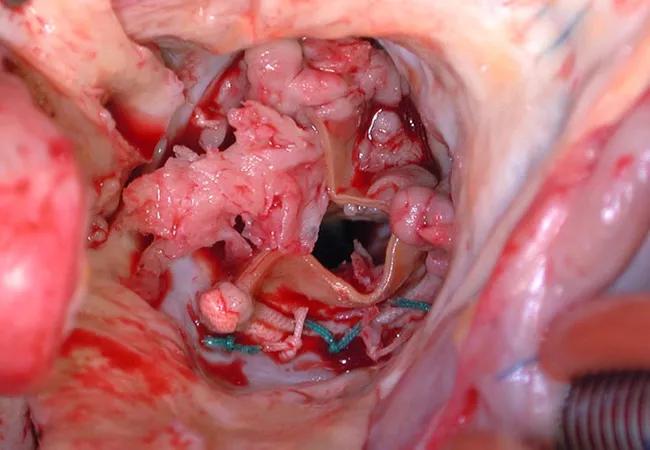

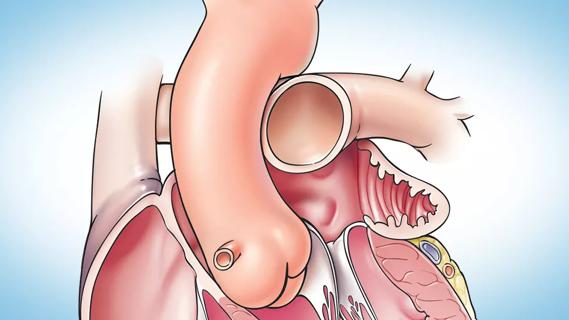

Unless successfully treated and cured, infective endocarditis is fatal. It is associated with septic embolism (systemic with left-sided infective endocarditis and pulmonary with right-sided infective endocarditis), destruction of valve tissue and invasion outside the aortic root or into the atrioventricular groove. Antimicrobials kill sensitive and exposed organisms but cannot reach those hiding in vegetations or biofilm, on foreign material or in invaded extravascular tissue.

The objectives of surgery are to eliminate the source of embolism, debride and remove infected tissue and foreign material, expose and make residual organisms vulnerable to antimicrobials, and restore functional valves and cardiac integrity. Surgery to treat infective endocarditis is difficult and high-risk and requires an experienced surgeon. But final cure of the infection is still by antimicrobial treatment.

Every aspect of infective endocarditis — diagnosis, medical management, management of complications, and surgery — is difficult. Recent guidelines1-5 therefore favor care by a multidisciplinary team that includes an infectious disease specialist, cardiologist and cardiac surgeon from the very beginning, with access to any other needed discipline, often including neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology and dependence specialists.

Patients with infective endocarditis should be referred early to a center with access to a full endocarditis treatment team. The need for surgery and the optimal timing of it are team decisions. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery infective endocarditis guidelines are question-based and address most aspects that surgeons must consider before, during and after operation.1

Advertisement

Once there is an indication to operate, the operation should be expedited. Delays mean continued risk of disease progression, invasion, heart block and embolic events. Determining the timing of surgery is difficult in patients who have suffered an embolic stroke — nonhemorrhagic or hemorrhagic — or who have suffered brain bleeding; management of these issues has recently triggered expert opinion and review articles.6,7

The recommendation for early surgery is based on the conviction that once the patient has been stabilized (or has overwhelming mechanical hemodynamic problems requiring emergency surgery) and adequate antimicrobial coverage is on board, there are no additional benefits to delaying surgery.8 When the indication to operate is large mobile vegetations associated with a high risk of stroke, surgery before another event can make all the difference.

In the operating room, the first aspect addressed is adequate debridement. There is wide agreement that repair is preferable to replacement for the mitral and tricuspid valves, but there is no agreement that an allograft is the best replacement option for a destroyed aortic root, although that approach is favored by our team. The key is that surgeons and their surgical teams must have the experience and tools that work for them.

Our recommendation is to refer all patients with infective endocarditis to a center with access to a full team of experienced experts able to address all aspects of the disease and its complications.

Advertisement

This article is slightly adapted from an editorial published in Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (2018;85:365-366).

Advertisement

Drs. Pettersson and Blackstone are in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Dr. Griffin is in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and Dr. Gordon is Chair of the Department of Infectious Disease.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

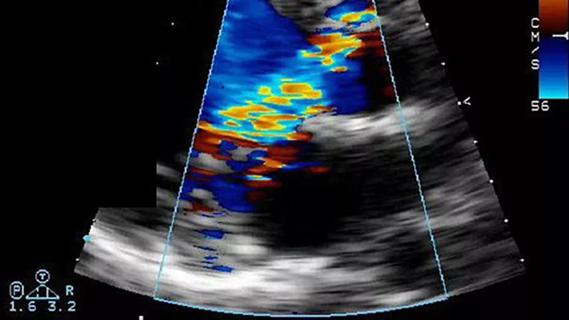

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

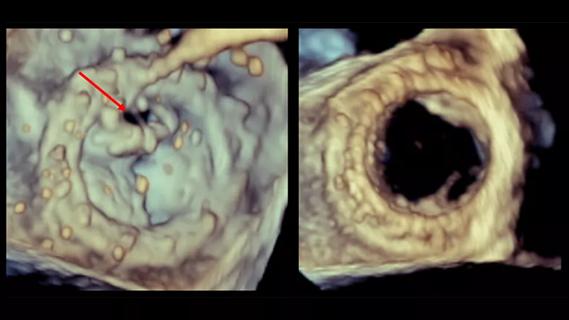

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

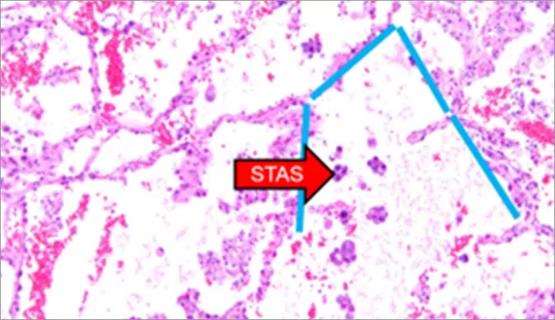

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable