The key is pursuing them all at once

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Heart transplantation is the most effective treatment for end-stage heart failure. Unfortunately, the supply of donor hearts does not meet demand. Many patients die on the wait list.

The transplantation community recently took strides to address this issue. In January 2016, the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation published updated guidelines for transplant candidacy. That same month, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) issued its proposal to change adult heart allocation.

These efforts are much needed. However, they address only parts of the problem. The only way to properly match the transplant market is to simultaneously do the following:

In an editorial recently published in Circulation: Heart Failure, I explore each of these elements, comparing strategies in the U.S. to those in other countries. Based on my findings, the U.S. transplantation community should consider the following three-pronged strategy.

Most centers consider an ideal donor as younger than age 40 and without the following:

Registering more of these ideal donors is one way to increase the donor pool. We could do this by changing our current opt-in system (in which people must proactively register as an organ donor) to a presumed-consent, opt-out system. Offering incentives and increasing social awareness would help as well.

Advertisement

However, we also could better use the donated organs we already receive. Today, we refuse two-thirds of organs because donors don’t meet ideal criteria. This is not always necessary.

Instead of discarding these organs, we should categorize them in one of two ways:

The heart transplant guidelines we’ve used for decades include very few contraindications. As a result, candidates on today’s wait list are older and have more comorbidities relative to their counterparts from years past. Some are tobacco users. Some have end-organ damage from diabetes mellitus.

Unfortunately, the “lifeboat” for advanced heart failure will sink if it attempts to hold everyone. We need to tighten eligibility and standardize it across centers, thus preventing patients ineligible at one center from seeking listing at another.

Advertisement

Certainly, tightening eligibility is difficult. Criteria should be based on data that indicate poorer outcomes: age over 70, active tobacco use and renal insufficiency, for example. There are many ethical considerations as well, such as retransplantation and dual organ transplantation.

Ventricular assist devices (VADs) should be considered more widely as a transplant alternative, especially for patients expected to have similar survival with either treatment.

Women, Hispanics and patients with restrictive or congenital heart disease are more likely to die on the wait list than are men, whites and those with either ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy.

The new system proposed by the OPTN Thoracic Committee could address some of these disparities by incorporating more tiers based on medical urgency.

Another option is to create an allocation score, such as the scores used in liver and lung transplantation. To create this type of algorithmic system, risk factors must be identified — a substantial task given the number of variables and high-risk subgroups.

Increasing the donor pool, reducing the wait list and improving the allocation system are necessary to better satisfy U.S. demand for heart transplantation. Although it is easier to focus on one strategy, all three must be pursued simultaneously.

Collaboration between medical and community participants will be vital in order to rebalance supply and demand.

Dr. Hsich is Director of the Women’s Heart Failure Clinic and Associate Medical Director of the Heart Transplant Program at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

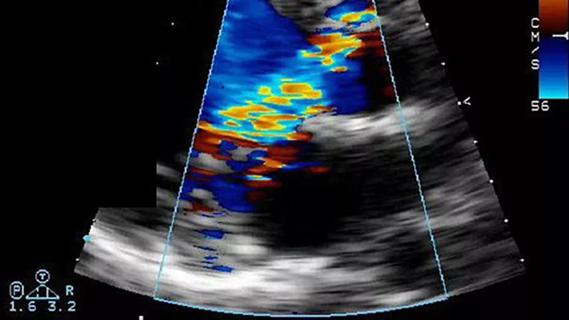

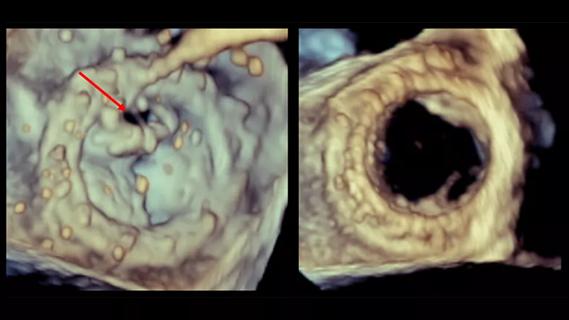

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

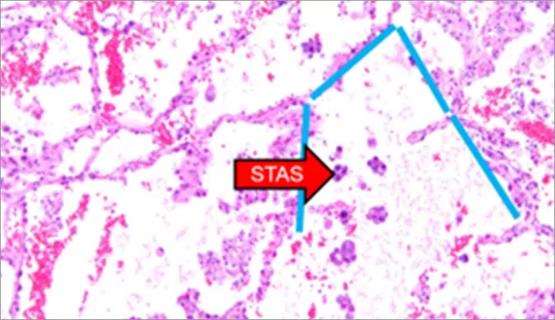

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable