Main utility may lie in initiating patient conversations

How useful are heart disease risk calculators in assessing risk and deciding whether to prescribe statin therapy?

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“The bottom line is that these calculators are far from perfect, but they’re a starting point to assess risk and open a discussion about whether therapy is appropriate,” says Michael Rocco, MD, Medical Director of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Stress Testing in the Section of Preventive Cardiology at Cleveland Clinic.

He notes that according to a recent study of five such risk calculators in the Annals of Internal Medicine, all the calculators substantially overestimated risk except for the Reynolds Risk Score. The new ASCVD Risk Estimator (based on the Joint Guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association) and three older Framingham-based risk scores overestimated cardiovascular events by 37 to 154 percent in men and by 8 to 67 percent in women. Notably, the use of preventive therapies did not seem to be the reason for the over predictions observed.

Evaluation of the ASCVD Risk Estimator was a key objective of the Annals study, in light of prior reports that it overestimated cardiovascular risk. In developing the ASCVD calculator, the ACC and the AHA aimed to create a more reliable tool by including African-Americans in the population and including cerebrovascular disease, stroke and stroke-related deaths as well as heart disease as the end points.

“The new calculator overestimates risk, but less so than the previous calculator we’ve been using for years as part of the ATP III [Third Adult Treatment Panel] guidelines,” Dr. Rocco says. “The data show that this new calculator overestimates risk, but that’s not necessarily a bad place to be for starting a discussion of whether or not to treat.”

Advertisement

“There is an inherent problem with any kind of risk calculator,” he notes. “All the calculators are developed based on data from certain populations and then applied to broader populations. So there is always going to be some misrepresentation if you apply it to a different subgroup of patients that aren’t well represented in the original data.”

In some cases, using more than one risk tool might be a good idea, he adds. “If you’re going to add one, the Reynolds Risk Score is reasonable to consider because, unlike many of the others, it takes into account family history and ultra-sensitive CRP, and in the recent Annals study it seemed to track better in a more contemporary multiethnic patient group.”

“It’s not so bad if we overestimate a bit,” Dr. Rocco continues, “because meta-analyses show that even lower-risk patients can benefit from statins; it just takes longer to show a benefit. On the flip side, however, is the argument that over treating exposes patients needlessly to the side effects of the drug. That’s why it’s important from a clinical perspective to use these calculators as a starting-point tool when deciding on treatment in a primary prevention patient.”

For example, he says, if an individual patient slightly exceeds the risk cutoff (7.5 percent over 10 years for the ASCVD Risk Estimator) but otherwise has a favorable profile, treatment with medications might not be warranted and a focus on lifestyle intervention might be more appropriate.

On the other hand, a young person with an LDL cholesterol level of 165 mg/dL and a low estimated short-term risk who has a strong family history and a lifetime risk of over 50 percent might well be a candidate for therapy. “Using other risk markers, such as this person’s ultra-sensitive CRP or even a coronary artery calcification score, may help reclassify risk further,” says Dr. Rocco. “If those markers are abnormal, initiation of statin therapy would be appropriate.”

Advertisement

He adds that a particular risk score is not a mandate to treat or not to treat but rather an opportunity to initiate a dialogue regarding risks and benefits of treatment for a specific primary prevention patient. “Treatment decisions need to be individualized.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

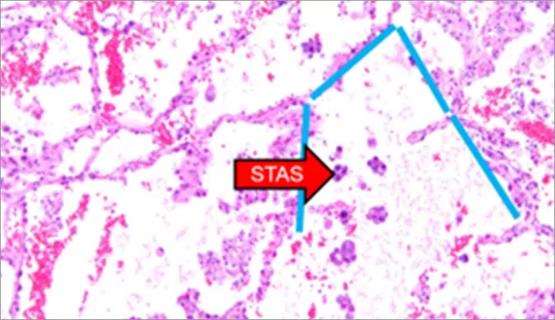

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable