Patients can go home the same day

The number of gastric bypass surgeries continues to rise around the country, creating a larger and larger population of patients with altered anatomy around the stomach and intestines. As a result, physicians are discovering new challenges to treating these bariatric patients when they experience illness involving organs near that altered anatomy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

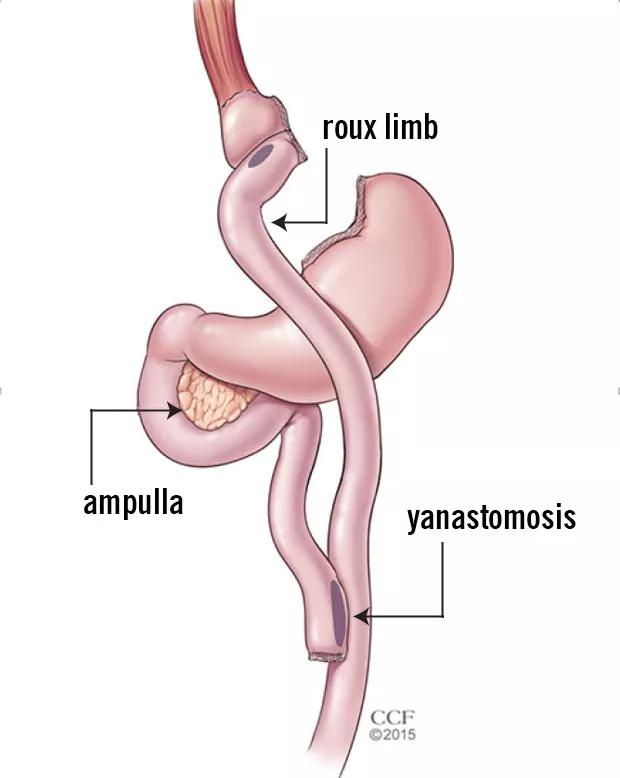

“The way the anatomy becomes structured after bypass surgery is there’s a tiny pouch at the end of the esophagus with the rest of the stomach excluded, stapled off,” says advanced endoscopist Prabhleen Chahal, MD. “The pouch is connected to a loop of small bowel (Roux limb) which leads to a ‘Y’ shaped anastomosis in the small bowel (see image below). The biliopancreatic limb leading to excluded stomach is attached to this Y intersection. The total length of small bowel from the pouch to the excluded stomach is between 150 to 200 cm in long limb bypass.

Because of this anatomy, she says, it is very difficult to reach the ampulla (opening of bile duct and pancreas) and excluded stomach. “It’s a long, long way endoscopically,” she says.

To get around this problem, physicians often perform a technique called laparoscopic-assisted ERCP (LAERCP). This procedure requires the combined efforts of a surgeon and an advance endoscopist. The surgeon makes an incision in the belly to find the excluded part of the stomach and bring it up closer to the abdominal wall. Then the surgeon makes an incision and inserts a port through which the endoscope can fit. If the patient needs a repeat procedure, a large caliber percutaneous feeding catheter (PEG) tube is left through the access site in the abdomen. The patient is brought back weeks later and the entire procedure is repeated in the operating room with the assistance of surgeons.

“It can be risky and requires about one to two days of hospitalization” Dr. Chahal says, “which is why we were eager to try something new.”

Advertisement

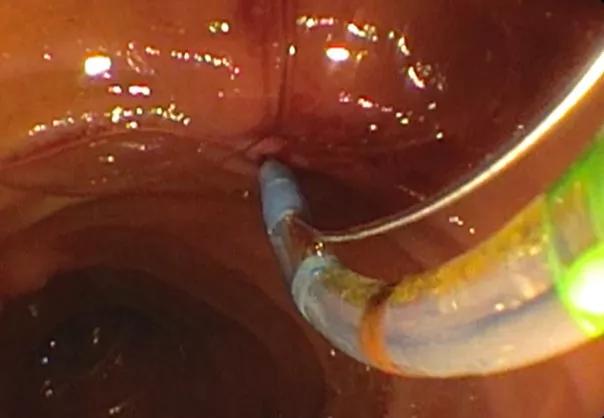

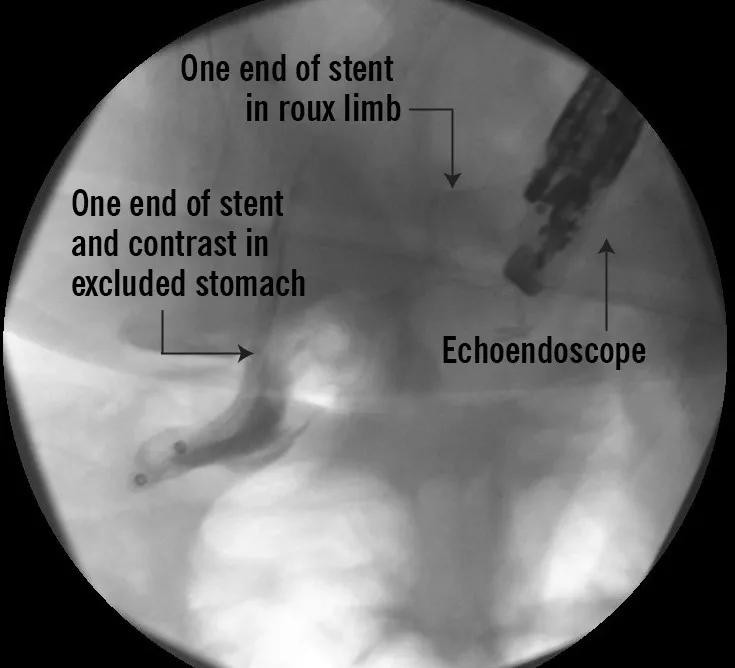

In April, Dr. Chahal performed Cleveland Clinic’s first endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP, known as EDGE, in its outpatient endoscopy unit. Physicians used a special endoscope fitted with a camera and a small ultrasound probe. This equipment allows them to visualize the excluded stomach from the gastric pouch or roux limb. Then they create an opening or fistula with a small needle and insert a lumen-opposing metal stent (a dumb-bell shaped, removable metal stent), which creates a 1.5 to 2 centimeter opening.

“One end of stent is in the gastric remnant and the other end comes out into the pouch or roux limb,” Dr. Chahal says. “So basically we’ve recreated the normal route and we have easy, simple, straight access like we do with all the normal anatomy patients.”

If the patient needs multiple procedures, she says, physicians can leave the stent in place so that they can go in with an endoscope as many times as they need. When all the procedures are finished, the doctor removes the stent and cauterizes the area, sealing up the fistula that was created.

Dr. Chahal says it took 40 minutes to do the procedure and her patient was discharged the same day and allowed to eat afterward.

So far, Dr. Chahal has successfully performed four EDGE procedures. Her first case was a 46- year-old woman who had undergone gastric bypass surgery in 2003. From October 2017 to April 2018, the patient had several documented episodes of acute pancreatitis and was diagnosed with pancreas divisum, where the pancreatic duct opens separately from the bile duct in an area called the minor papilla. Images showed that the woman’s pancreatic duct was significantly dilated, which meant she had scarring on the opening of the pancreatic duct and the minor papilla.

Advertisement

Using the EDGE procedure, Dr. Chahal says she was able to reach the ampulla and locate the patient’s minor papilla where she made a small slit to relieve the obstruction and open the scar tissue. Shen then inserted a stent to keep it open. Post-procedurally, the patient ate normally and had no complaints. She returned to clinic four weeks later and the stent was removed uneventfully.

Dr. Chahal believes EDGE will eventually replace LAERCP at Cleveland Clinic. “I always give patients both options and let them make the decision,” she says. “All of my patients opted for EDGE, where there is no catheter or tubes hanging from their belly and they are discharged home the same day with a comparable, if not superior, risk profile when compared with LAERCP.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Strong patient communication can help clinicians choose the best treatment option

ctDNA should be incorporated into care to help stratify risk pre-operatively and for post-operative surveillance

The importance of raising awareness and taking steps to mitigate these occurrences

New research indicates feasibility and helps identify which patients could benefit

Treating a patient after a complicated hernia repair led to surgical complications and chronic pain

Standardized and collaborative care improves liver transplantations

Fewer incisions and more control for surgeons

Caregiver collaboration and patient education remain critical