New revision aligns with other major guidelines’ recommendations

The new draft guidance on low-dose aspirin from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is a welcome development, even if it’s late in coming. That’s the view of leading Cleveland Clinic clinicians in response to the USPSTF’s recommendation statement, “Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease: Preventive Medication,” issued in mid-October for public comment through Nov. 8.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has been out of step with other organizations on the issue of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but now they’re coming into alignment with what almost everyone else has been saying,” observes Steven Nissen, MD, Chief Academic Officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute.

The draft USPSTF guidance recommends against starting low-dose aspirin (81 mg) for primary prevention of CVD in individuals aged 60 or older. For primary prevention in those 40 to 59 years old who have a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%, the draft guidance says starting low-dose aspirin is an individual decision to be made in consultation with one’s physician.

The new recommendation revamps the 2016 USPSTF guidance on low-dose aspirin for primary prevention, which recommended it for individuals in their 50s with a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk and called for individualized decisions for those in their 60s with similar risk.

The proposed changes bring the USPSTF advice closer to the 2019 guideline from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74 :e177-e232), which states that low-dose aspirin for primary prevention may be considered in adults aged 40 to 70 who are not at increased bleeding risk but should not be used in those older than 70. The ACC/AHA guideline specifies that aspirin should not be considered for adults of any age who are at increased risk of bleeding.

Advertisement

The USPSTF panel appears to be responding to a series of large studies in the past few years. “There were three studies — ASPREE, conducted in patients aged 70 or older; ARRIVE, conducted in patients at moderate cardiovascular risk; and ASCEND, conducted in patients with diabetes mellitus — that help guide this decision,” says Leslie Cho, MD, Co-Section Head of Preventive Cardiology and Rehabilitation at Cleveland Clinic.

Dr. Nissen notes that the ASPREE trial, for instance, showed that the increased risk of gastrointestinal or brain bleeding from aspirin mostly counterbalanced any benefit from reduced risk of cardiovascular events in the primary prevention setting. “Mounting evidence indicates that unless a person’s 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event reaches 20% or more, they shouldn’t take aspirin for primary prevention,” he says. “Even then, any decision should be made in consultation with their physician.”

The language of the draft USPSTF guidance signals increased recognition of the risks of aspirin use. For instance, the recommendation that it may be considered for adults 40 to 59 with ≥ 10% CVD risk over 10 years is followed by a disclaimer that “the net benefit of aspirin use in this group is small.”

Those types of nuances — such as the fact that the ACC/AHA guideline recommends consideration of aspirin in moderate-risk individuals whose risk factors are not well controlled — are further reason why patients should recognize that any aspirin-related decisions must be made with their physician’s guidance, Dr. Cho emphasizes.

Advertisement

Even with these shifts toward consensus opinion on the risk-benefit profile of aspirin for primary prevention, the draft USPSTF guidance still harbors some areas of confusion, according to Dr. Nissen. Chief among them is the focus on recommending against initiation of aspirin therapy while allowing continuation of existing aspirin therapy in the same patient groups. “I think this distinction between initiation and continuation will be confusing to people, because the risks are the same,” he says.

While Dr. Nissen has been a long-time advocate of restraint in the use of aspirin for primary prevention, he emphasizes that low-dose aspirin is well established and widely recommended for use in secondary prevention of CVD. “The value of aspirin for that indication must not get lost in this discussion,” he says.

“At the same time, clinicians should be mindful of the imperative to avoid aspirin in any individuals with increased risk of bleeding,” Dr. Nissen adds. That includes those over age 70 and patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer disease, bleeding from other sites, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy or chronic kidney disease. It also includes patients currently taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids or anticoagulants. “There are many people for whom the risks of bleeding from aspirin simply exceed the benefits,” he concludes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

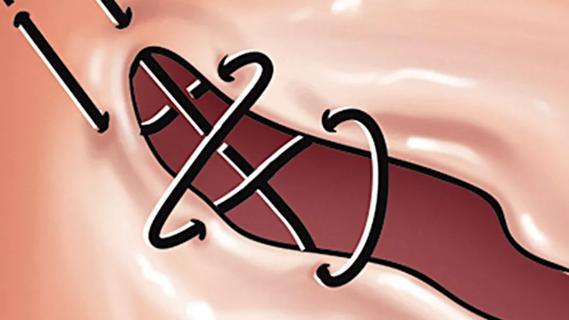

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

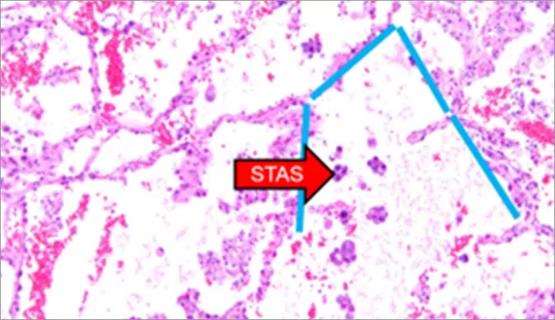

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable