Patients need less opioids and go home sooner

Housed within Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Pain Management, the Acute Pain Management Service (APMS) uses state-of-the-art, evidence-based pathways proven to reduce postoperative pain, involving combinations of nerve block, epidural, intravenous and multimodal analgesic drug therapies.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The APMS is one of few in the country with a dedicated multidisciplinary team that works 24/7.

The program is also unique in proactively identifying patients who are more likely to experience pain after surgery and intervening in advance. What’s more, the APMS team pioneered the practice of sending patients home with indwelling catheters, allowing for minimal use of sedating oral medications and reducing length of hospital stay.

Pain management programs are most often run by surgeons or anesthesiologists, or by the nursing staff. At Cleveland Clinic, the team involves surgeons, anesthesiologists, pharmacy, nurses, nurse managers, nurse practitioners and physical therapists, comprising about 30 individuals in all.

“We all collaborate to deliver the same message to the patient,” says APMS founder and director Loran Mounir Soliman, MD, who joined Cleveland Clinic’s anesthesiology department in 2006 and began building the APMS the following year. Dr. Soliman is also director of the acute pain/regional anesthesia fellowship.

The elaborate infrastructure sets Cleveland Clinic’s acute pain management program apart from others, says anesthesiologist Kamal Maheshwari, MD, who joined APMS in 2009. “This is a huge service with unparalleled infrastructure and focus on keeping patients safe and comfortable.”

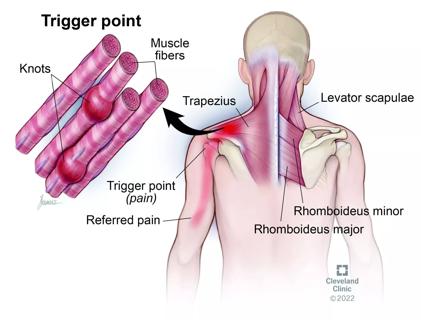

Ineffective treatment of postoperative pain can lead to many negative outcomes, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, poor wound healing and insomnia. Those complications raise costs, prolong hospital stays and prompt readmissions. One study found that pain was the most common reason for readmission following same-day surgeries in the U.S., accounting for about 38 percent of the total.

Advertisement

At Cleveland Clinic, where about 45,000 surgeries are performed annually, that percentage is far lower. This is in large part because of the APMS, which serves between a fifth and a quarter of patients undergoing surgery at the institution.

Patients referred to the APMS fall into several categories:

Patients in the first two categories meet with the APMS prior to their procedures. According to Dr. Soliman, “Our program is unique in trying to identify patients who might have issues with pain control, so we have a chance to discuss options and what to expect after surgery. We educate patients to set realistic expectations for how to cope with pain in the first few days. We do that for patients upfront.”

The APMS team has developed several pain management pathways, including those following upper abdominal procedures, total knee and shoulder replacements, and spine surgeries. More pathways are being developed, and the current ones are revised on an ongoing basis.

Advertisement

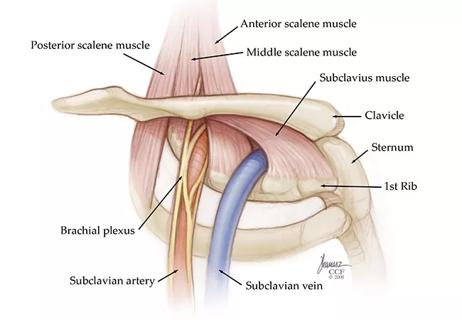

These pathways involve step-wise patient evaluations and use of surgery-specific pain control modalities. For example, extremity surgery usually involves nerve blocks, while surgery in the abdomen or thorax typically will require epidural infusion. Following head and neck surgery, patients receive multimodal analgesia, combining two or three drugs from different classes, aiming for the fewest side effects from each.

According to Dr. Maheshwari, “Joint replacements, especially total knee replacements, result in significant pain, but we make patients comfortable by using specific nerve blocks. The same goes for ankle and shoulder surgery. Patients used to stay in the hospital three to four days just for pain control. Now they go home the same day if they want, or maybe the next day.”

Orthopaedic surgery patients are able to leave the hospital so soon because they take their pain meds home with them, via indwelling peripheral nerve catheters and a disposable pump containing the anesthetic. Nurses call patients every day for a week to make sure things are going as planned.

“We have the ability to follow up with patients while they are at home and troubleshoot any issues. That’s how we reduce length of stay. Patients are staying with their family more, which helps in their recovery,” says Dr. Maheshwari.

“Every day of hospital stay adds cost and complications. The hospital is safe, but there’s always the chance of hospital-acquired infection and other complications. Also, if patients are consuming less opioid medication because of the nerve blocks, the recovery is much faster,” he notes.

Advertisement

Data collected pre- and post-APMS validate the program’s success. On discharge from the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) following total knee replacements, for example, patients reported significantly reduced pain on the Visual Analog Scale, 2 versus 4 points (P < 0.005). Opioid use in the PACU also was reduced, at 2.9 compared with 14.6 morphine equivalents in milligrams (P < 0.007).

Patients were discharged from the PACU in an average of 4.1 hours compared with 6.4 hours postsurgery (P < 0.001) and had shorter average length of overall hospital stay, 2.1 versus 4.5 days (P < 0.001).

Importantly, total knee replacement patients who received APMS care had better function at six months after the procedure, with Knee Scoring System scores of 59.4 versus 46.9, a significant difference at P < 0.05.

None of this would be possible without extensive staff collaboration. Development of each pain management pathway involves several initial meetings to make sure all team members understand their roles and the application of the pathway. Then there are meetings to revise any problem areas. For example, the nurses need to be clear on what they will be teaching the patient regarding their pain, and physical therapy has to know what approaches to use.

Meetings to develop pathways are usually held monthly for the first six months, then less frequently. “Along the course, you do change your original plan. There is constant updating of the pathways,” says Dr. Soliman.

Indeed, says Dr. Maheshwari, “It’s a dynamic practice. We adapt to patient needs, and to the data. The goal always is better patient outcomes.”

Advertisement

Here’s Dr. Soliman’s advice to other institutions interested in creating a similar program: “You have to have agreement among all the stakeholders who care for the patient and commitment that they will comply with the plan. You can’t say you’re running late so you’ll skip it. You’ve made a commitment to the patient.”

Dr. Maheshwari can be reached at maheshk@ccf.org or 216.445.4311. Dr. Soliman can be reached at mounirl@ccf.org or 216.445.4868.

Advertisement

Two-hour training helps patients expand skills that return a sense of control

Program enhances cooperation between traditional and non-pharmacologic care

National Institutes of Health grant supports Cleveland Clinic study of first mechanism-guided therapy for CRPS

Pain specialists can play a role in identifying surgical candidates

Individual needs should be matched to technological features

New technologies and tools offer hope for fuller understanding

Pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment and a COVID-19 connection

Clinical judgment is foundational to appropriately prescribing