Helps study various boundary and loading conditions

By Prasath Mageswaran, PhD, and Edward Benzel, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Computational modeling, which can be used to create virtual prototypes of the human anatomy, is a valuable tool for assessing physical structures. In the Spine Research laboratory at Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Spine Health, our investigators are developing accurate and fully validated computational models of the human spine. These models will allow us to study the behavior of the spine under various boundary and loading conditions. They also will provide clinicians with the ability to engage in virtual diagnosis, assessment and presurgical planning prior to the actual implementation of care. Virtual rendering of the spine can be useful to researchers as well as clinicians.

What makes computational modeling so vital is that traditional physical testing methods of the spine (both in vivo and in vitro) are less than ideal. For example, some techniques require the testing of animal or human cadaveric specimens in a machine, which is expensive and time-consuming. In addition, in vivo studies can pose ethical dilemmas and concerns about the accuracy of data and the extrapolation of results to human situations. Obviously, normal healthy human spines are not readily available for in vitro testing. Furthermore, the loads and muscle forces that are active in normal spine motion cannot be reliably replicated, and the distribution of internal stresses and strains within specific tissue components cannot be measured accurately.

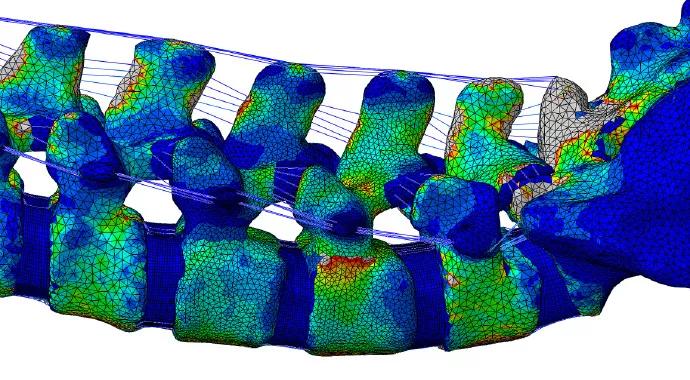

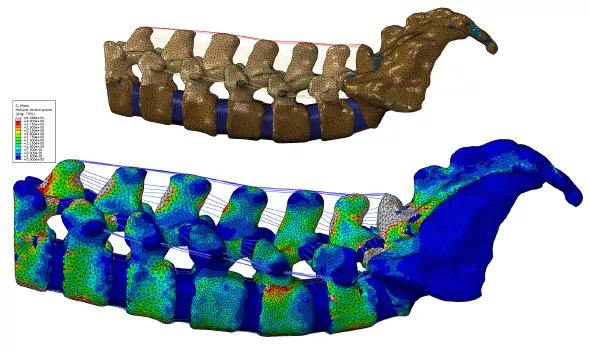

A computer model of the spine has the advantages of providing useful information about a spine’s response to external loads as well as the ability to predict the internal stresses and strains that occur (Figure 1).

Advertisement

FIGURE 1. (Top) Computer model of the spine showing various structures, and (bottom) virtual simulation using color coding to show various levels of stress on the spine with highly precise localization. The highest levels of stress are indicated by gray (and then by red); the lowest levels are indicated by dark blue.

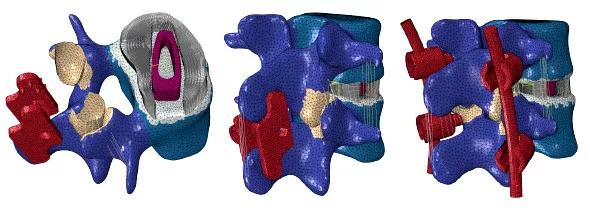

Spinal stability following the placement of various implants (e.g., an interspinous device) can be simulated and analyzed, providing clinicians with insight into the potential performance of specific implants before the actual surgery.

One of the models being developed in our Spine Research laboratory is a multisegment lumbar spine. This model can be used to simulate and evaluate various clinical scenarios, such as the extent of degeneration, the biomechanical efficacy of surgical procedures (e.g., laminectomy and fusion) and the placement of implants for stabilization (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Computer spine models with various spinal implants (shown in red).

Once a general model is validated, patient-specific versions can be developed quickly to aid clinicians in their decision-making process regarding the management of spinal ailments.

A ground-up approach is used typically for the development of a computerized spine model. It begins with the acquisition of CT scans to define the geometry of the vertebrae, which represent the hard tissue elements. The geometry of the hard-tissue elements is converted to a 3-D model. Then the soft-tissue elements ‒ intravertebral discs, ligaments and muscle ‒ are added to the model, based on their CT dimensions. The upper and lower areas of the disc model are matched to the contours of the upper and lower endplates where the disc abuts the vertebrae. The insertion points for the ligaments are estimated on the basis of MRI data.

Advertisement

Following construction of the model, material properties are assigned to each of the distinct anatomic elements. In concert, all these elements establish a basis for insight into the relationship between an applied spinal load and the resultant deformation experienced by each of the spine’s component materials.

Spinal implants are designed to function as either fusion-enhancing devices or motion-preserving devices. The primary objective of fusion-enhancing devices is to stabilize a dysfunctional or damaged spinal segment by completely restricting its motion. Motion-preserving devices, such as an artificial disc, are intended to preserve the normal function of a spinal segment.

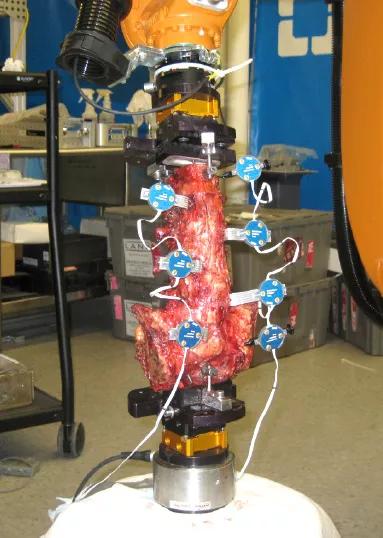

Once one of these models is developed, it must be validated. One of the ways our team of clinicians and engineers achieves this is by analyzing precisely controlled experimental test data obtained from a robotic spine testing system (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Robomechanical spine testing.

The accuracy of a computer model’s predictions can be validated by comparing the prediction with a set of known data obtained through in vivo and in vitro tests. If the results are not comparable, changes are made to the material properties of the model.

The flexibility of computational modeling allows us to make changes rapidly. The effect of various design parameters, such as shape, size, location of placement and material properties, can be altered to determine an optimal design. The validation process is repeated until comparable results are obtained.

Advertisement

By using these sophisticated computational models, we hope to gain a better understanding of the interaction between the spine and various spinal implants. We also are expanding our research domain to include modeling of previously unstudied regions of the spine.

Dr. Mageswaran is a research engineer in the Spine Research Laboratory at Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Spine Health.

Dr. Benzel is Chairman of Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Neurological Surgery and a staff physician in the Center for Spine Health.

Advertisement

Advertisement

New study advances understanding of patient-defined goals

Testing options and therapies are expanding for this poorly understood sleep disorder

Real-world claims data and tissue culture studies set the stage for randomized clinical testing

Digital subtraction angiography remains central to assessment of ‘benign’ PMSAH

Cleveland Clinic neuromuscular specialist shares insights on AI in his field and beyond

Findings challenge dogma that microglia are exclusively destructive regardless of location in brain

Neurology is especially well positioned for opportunities to enhance clinical care and medical training

New review distills insights from studies over the past decade