Principles for finding effective regimens among the many options

By Lara Jehi, MD, and Zhong Ying, MD, PhD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Mr. D, 49 years old, has had seizures for the past 15 years. They begin with a “strange feeling in the head” and difficulty concentrating. He then turns pale, has chewing movements and becomes unresponsive. In rare instances, the seizure evolves to a generalized tonic-clonic convulsion. EEG and MRI studies have been normal, and focal epilepsy was diagnosed based on his seizure features, including aura.

He was treated initially with phenytoin for five years, during which time he continued to have one or two seizures per month. Over the ensuing years, various medications were tried in different combinations (phenytoin plus topiramate, topiramate plus levetiracetam) in an attempt to achieve better seizure control, but his clinical picture remained the same. With the combination of topiramate plus lamotrigine, seizures decreased to one or two per year, but Mr. D’s goal was to eliminate the seizures entirely. The next regimen, zonisamide plus lamotrigine, was also unsuccessful, and over the next four years his seizures persisted and gradually increased to one to two per month.

What should be the next step?

When considering a long-term treatment strategy for established epilepsy, it’s important to determine whether the condition is drug-responsive or drug-resistant. The complications of drug-resistant epilepsy should not be ignored: Sudden death from epilepsy occurs at a rate of 1 percent per year in these patients.

In 2010, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined drug-resistant epilepsy as the “failure of adequate trials of two tolerated, appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drug schedules (whether as monotherapies or in combination) to achieve sustained seizure freedom.” Key terms in this definition were defined as follows:

Advertisement

The rationale for the threshold of only two medications for defining drug-resistant epilepsy partially came from a landmark study published in 2000 that followed 470 patients with new-onset epilepsy. Initial treatment with an antiepileptic drug resulted in 47 percent of patients becoming seizure-free. For the remaining patients, adding a second drug led to an additional 13 percent response, while adding a third drug only helped another 4 percent.

A 2011 study looked at the problem in another way, following 246 patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. It found that over eight years, about one-third of patients achieved 12-month seizure remission with further medication adjustment. But after the year of remission, the risk of relapse was 71.2 percent at five years. The overall chance of sustained seizure freedom in this population was less than 10 percent.

According to the ILAE definition, Mr. D had drug-resistant epilepsy. Despite trying multiple different drugs, he had not achieved sustained seizure remission. It was recommended that he be evaluated for possible surgical intervention.

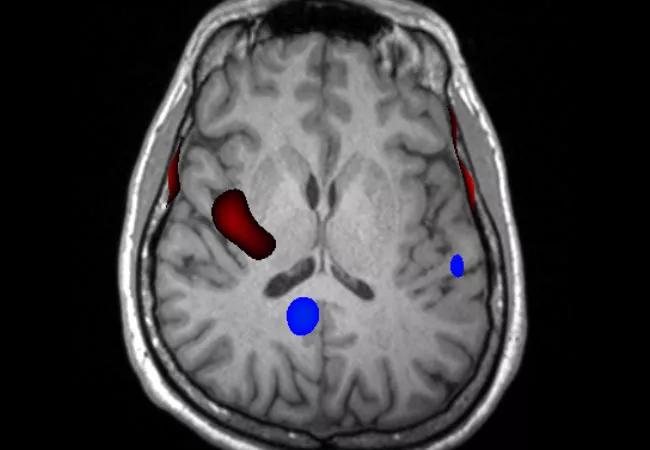

Video EEG showed no interictal spikes. Eight seizures were recorded but were difficult to localize. MRI was normal. PET showed bilateral temporal hypometabolism, with the left hemisphere more involved than the right.

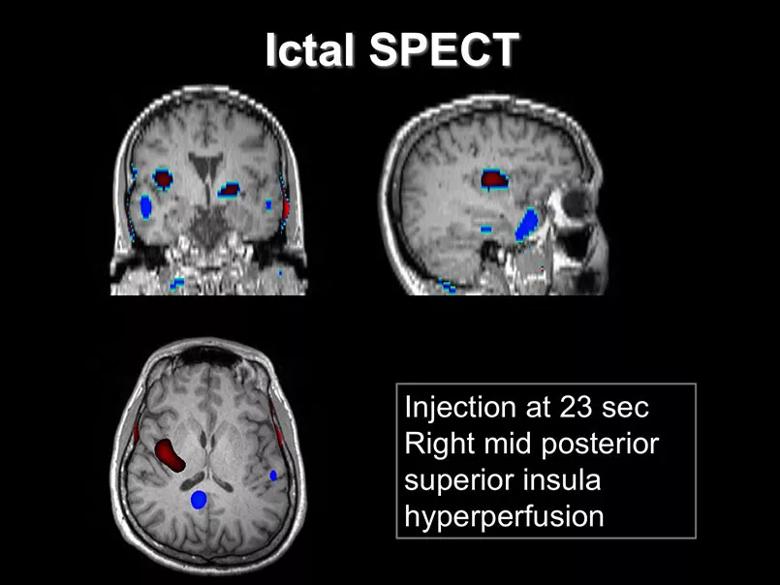

Ictal SPECT was performed with injection 23 seconds after seizure onset. Areas of hyperperfusion (red coloring in the image below) were found in the right mid-posterior superior insula.

Advertisement

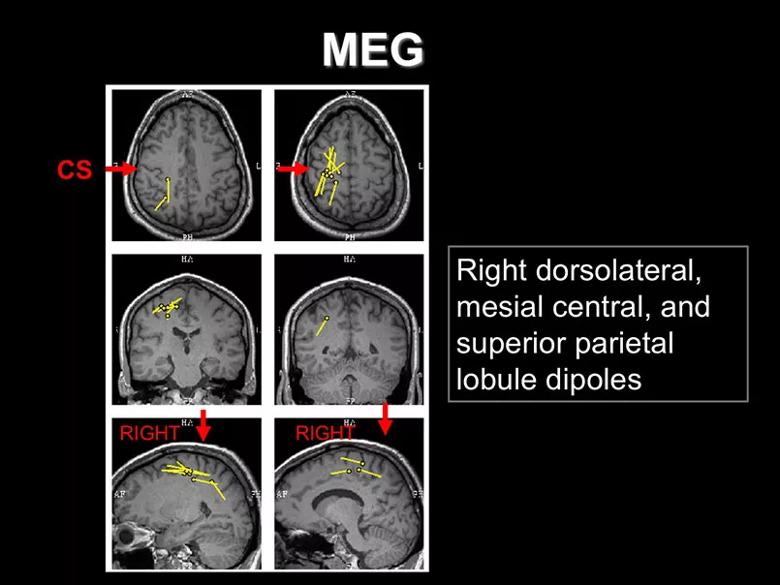

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) was performed in an attempt to further localize the patient’s epilepsy. It revealed dipole clusters in the dorsolateral, mesial central and superior parietal regions of the right hemisphere, as shown in the image below.

Overall, this presented a confusing picture. Clinical features, along with SPECT and MEG findings, indicated that the seizures likely originated in the right hemisphere. However, PET yielded bilateral findings, with the left side involved more than the right, while MRI and EEG revealed no localizing signs.

Mr. D was informed of the findings and told he could either proceed with trying to locate a surgically amenable area with invasive EEG or continue to pursue finding a more effective medication regimen. Neither option offered a high chance of success. He elected further medication adjustment.

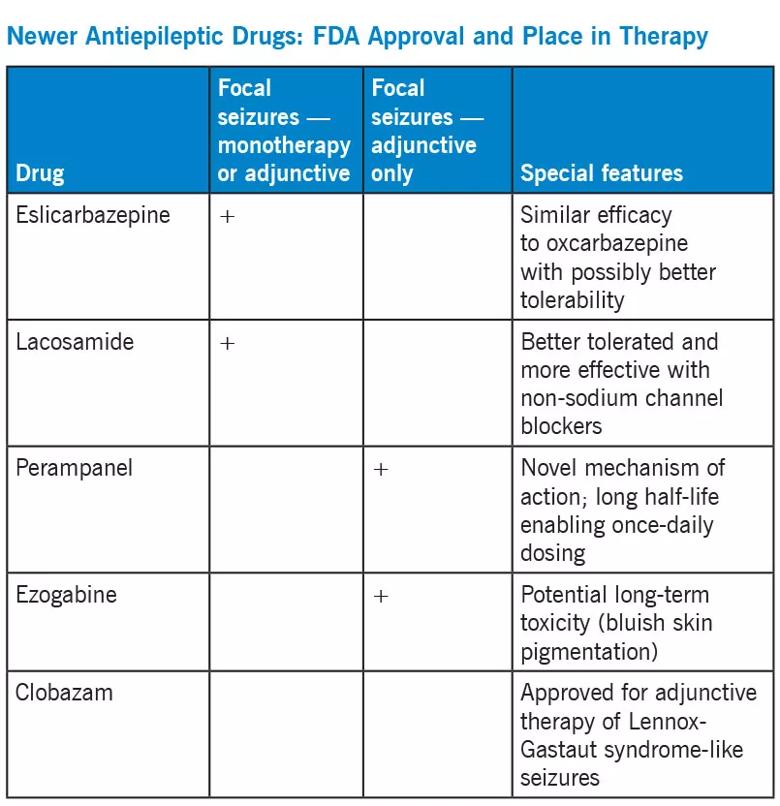

In the past 20 years, many new antiepileptic drugs have become available, a number of which had not yet been well-studied when the ILAE defined drug-resistant epilepsy in 2010. The table below presents the FDA-approved indications for five of the newer medications, along with specific special features that help guide management.

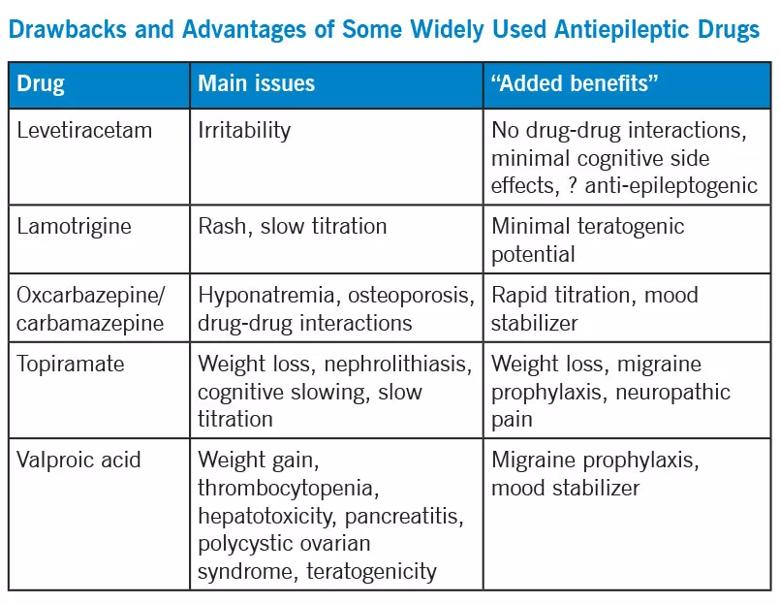

Within the FDA-approved indications, most antiepileptic drugs have similar efficacy. Choosing a specific therapy often depends on side effects, ease of use, potential interactions with other drugs and additional benefits that a drug may provide. The table below describes adverse effects as well as some “added benefits” of a few of the most commonly used antiepileptic medications.

Advertisement

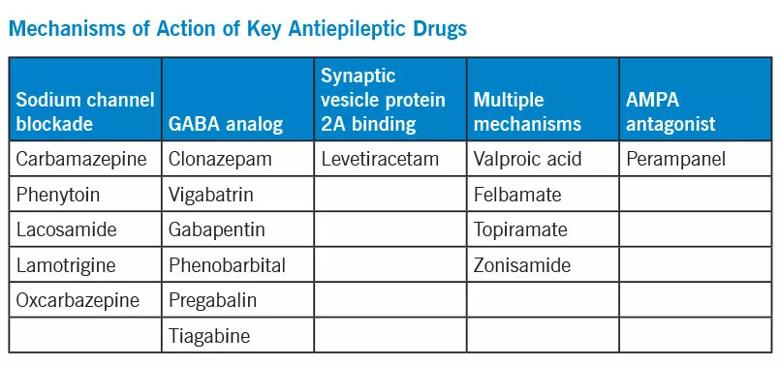

For combination therapy, it is important to consider each medication’s mode of action, with the general goal of combining different mechanisms of action to optimize efficacy and minimize side effects. The table below outlines the mechanisms of various antiepileptic drugs.

Mr. D’s drug regimen was changed from zonisamide plus lamotrigine to zonisamide plus lacosamide. He continued to have one to two seizures per month.

Clobazam was added. As a benzodiazepine, it was chosen because of the possibility that it might help him sleep at night. Because his seizures occurred mostly at night, he was anxious when he went to bed and usually slept poorly.

This turned out to be a successful combination: Mr. D has now been seizure-free for more than two years. Perhaps the success was at least partially due to the fact that clobazam’s mechanism of action differs from those of zonisamide and lacosamide.

At least two key points can be gleaned from this case:

Drs. Jehi and Yingi are epileptologists in Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center. Dr. Jehi reported that she consults for Lundbeck.

Advertisement

To view a webcast of this and nine other epilepsy cases in the “Hot Topics in Epilepsy for Children and Adults” CME-certified webcast series, visit ccfcme.org/EpilepsyCME. This activity has been approved for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™.

Advertisement

New study advances understanding of patient-defined goals

Testing options and therapies are expanding for this poorly understood sleep disorder

Real-world claims data and tissue culture studies set the stage for randomized clinical testing

Digital subtraction angiography remains central to assessment of ‘benign’ PMSAH

Cleveland Clinic neuromuscular specialist shares insights on AI in his field and beyond

Findings challenge dogma that microglia are exclusively destructive regardless of location in brain

Neurology is especially well positioned for opportunities to enhance clinical care and medical training

New review distills insights from studies over the past decade