Case shows why vigilance for stenosis is imperative

By Amar Krishnaswamy, MD; E. Murat Tuzcu, MD; Bryan Baranowski, MD; and Samir R. Kapadia, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 25-year-old man had been diagnosed with symptomatic atrial fibrillation and prescribed antiarrhythmic medications. When his rate and rhythm control remained inadequate, he was referred for pulmonary vein isolation at another institution. Within a few weeks of the procedure, he experienced onset of cough, mild left-sided chest discomfort and worsening dyspnea. He presented to Cleveland Clinic for further evaluation and management.

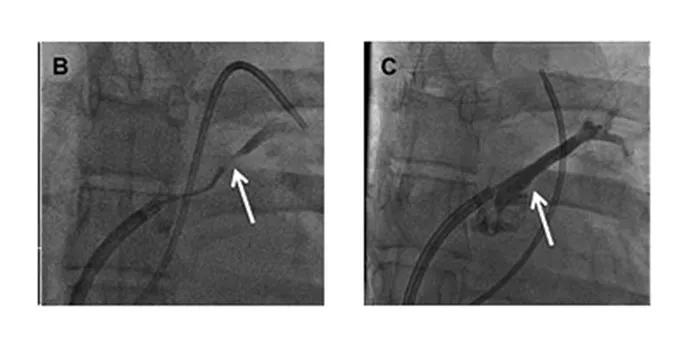

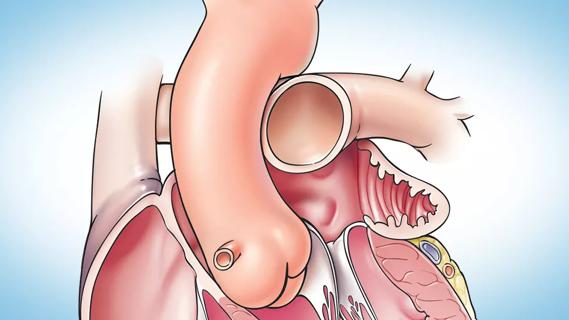

Figure A. Chest CT showing complete occlusion of the left superior pulmonary vein.

Chest X-ray was unremarkable, but chest CT demonstrated complete occlusion of the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV, Figure A). A nuclear perfusion scan of the lungs demonstrated a marked reduction in perfusion to the left upper lung field, concurrent with reduced drainage of the left upper lung due to the LSPV occlusion. Given the patient’s significant symptoms, he and the clinical team decided to treat the LSPV occlusion percutaneously.

The patient was brought to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. After sterile preparation and administration of local anesthesia and conscious sedation, venous access was obtained in the left femoral vein. An intracardiac echocardiography probe was introduced and advanced into the right atrium to facilitate transseptal puncture from right atrium to left atrium. Via access in the right femoral vein, a transseptal puncture needle was passed and advanced to the left atrium.

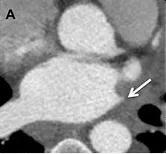

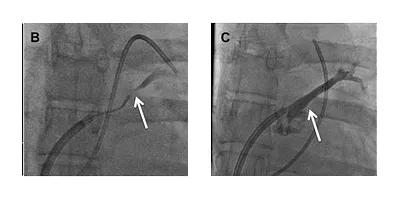

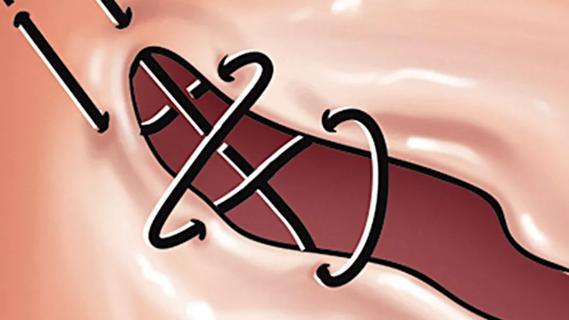

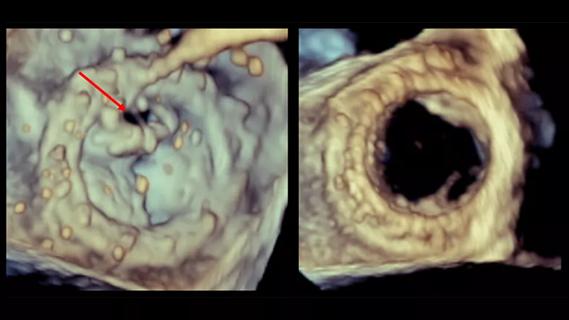

An angiogram of the left atrium demonstrated subtotal occlusion of the LSPV (Figure B). A wire was passed through the occlusion into the LSPV branches. A drug-eluting stent was then placed in the ostium of the LSPV, yielding complete patency of the vessel (Figure C).

Advertisement

Figures B and C. Angiograms of the left atrium demonstrating subtotal occlusion of the left superior pulmonary vein (B) and complete vessel patency following placement of a drug-eluting stent in the ostium of the left superior pulmonary vein (C).

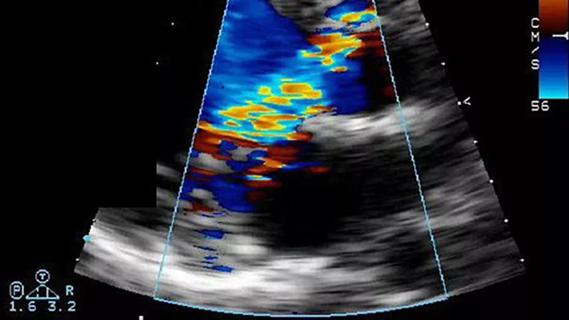

Figure D. Post-procedural chest CT demonstrating patency of the left superior pulmonary vein stent.

Follow-up CT demonstrated patency of the LSPV stent (Figure D). At one-year follow-up, the patient remained free of his presenting symptoms.

Severe pulmonary vein stenosis is seen in 1 to 2 percent of patients after pulmonary vein isolation. Although contemporary pulmonary vein isolation techniques have substantially reduced the incidence of this complication, vigilance in diagnosing pulmonary vein stenosis is important. We recommend routine CT scanning of the pulmonary veins three to four months after pulmonary vein isolation as surveillance.

Symptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis may present with coughing, hemoptysis and/or dyspnea. In this setting, treatment is beneficial for symptom relief. In patients with severe but asymptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis, the role of treatment is unclear. In patients who are asymptomatic but demonstrate significant perfusion defect on nuclear scanning, treatment may still be reasonable. Up to 10 percent of patients with a moderate degree of stenosis on CT at three-month follow-up may develop worsening stenosis by six to 12 months’ follow-up and should be subsequently evaluated.

Dr. Krishnaswamy (krishna2@ccf.org) is an interventional cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Tuzcu is an interventional cardiologist currently practicing at Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi; he helped manage this case when he practiced in Cleveland. Dr. Baranowski (baranob@ccf.org) is an electrophysiologist and interventional cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Kapadia (kapadis@ccf.org) is Section Head of Invasive and Interventional Cardiology at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A sampling of outcome and volume data from our Heart & Vascular Institute

Concomitant AF ablation and LAA occlusion strongly endorsed during elective heart surgery

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

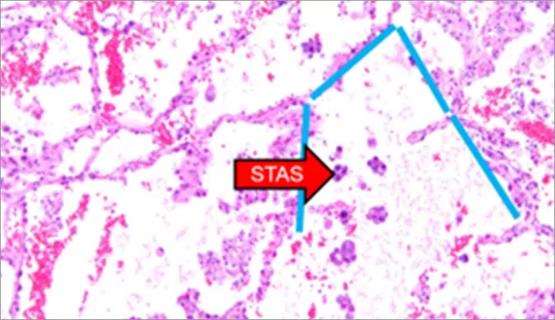

Young age, solid tumor, high uptake on PET and KRAS mutation signal risk, suggest need for lobectomy

Surprise findings argue for caution about testosterone use in men at risk for fracture

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Findings support emphasis on markers of frailty related to, but not dependent on, age

Provides option for patients previously deemed anatomically unsuitable