Case study and overview of knowledge to date

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 32-month-old girl presented to Cleveland Clinic Children’s for a second opinion on the etiology of white matter disease. Her medical history was unremarkable until she presented to an outside hospital at age 25 months with acute onset of ataxia without encephalopathy. Her condition was initially diagnosed at the outside hospital as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and treated with IV methylprednisolone. Brain MRIs at each of three separate presentations to the outside hospital over several months revealed new areas of demyelination. Initial CSF studies and spine MRI were normal.

Repeat brain MRI taken seven months later at Cleveland Clinic revealed new demyelinating lesions, and CSF analysis revealed elevated myelin basic protein, negative status for oligoclonal bands and neuromyelitis optica IgG antibody, and normal IgG synthesis. Extensive metabolic and mitochondrial studies were normal. A repeat brain MRI 24 months after initial presentation to the outside hospital showed two new white matter lesions.

The clinical presentation with multiple relapses without encephalopathy and multiple new white matter abnormalities on MRI validated a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, but as the child remained clinically asymptomatic on regular follow-up, her parents were reluctant to start treatment with disease-modifying agents.

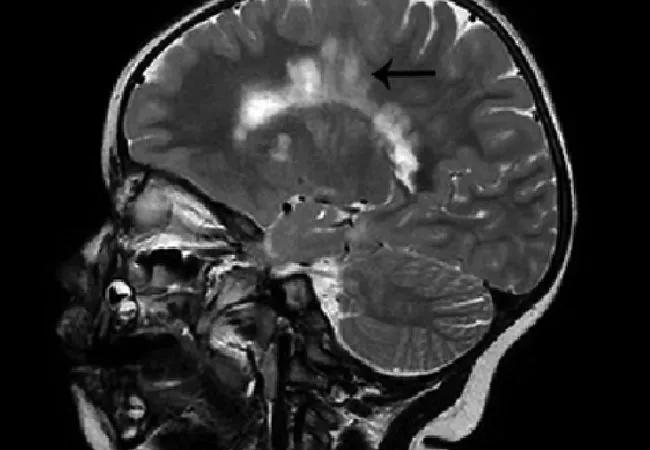

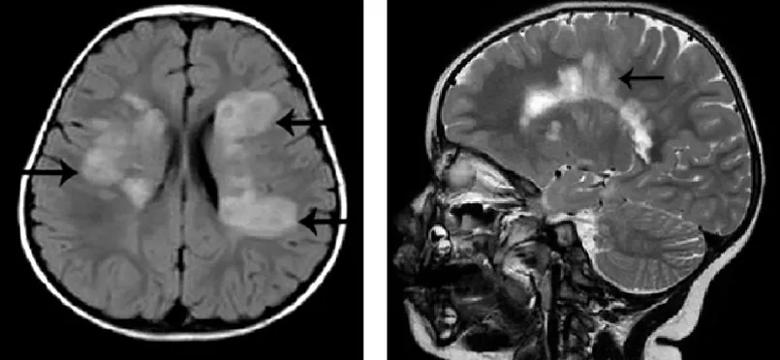

Figure. Brain MRIs in the case patient with arrows demonstrating extensive demyelination around the periventricular and deep white matter areas (left) and demyelinating plaques arranged perpendicular to the corpus callosum in a typical “Dawson fingers” pattern (right). Reprinted from Sivaraman and Moodley (Neurodegen Dis Manag. 2016;6:31-36) with permission of Future Medicine Ltd.

Advertisement

At the most recent clinical encounter, 33 months after initial presentation, the child remained clinically asymptomatic, but repeat brain MRI showed extensive white matter lesions — some new — involving the periventricular, pericallosal and subcortical areas.

This case, which we recently reported in detail along with a literature review (Neurodegen Dis Manag. 2016;6:31-36), illustrates the challenges of distinguishing among acquired inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the CNS in young children. These conditions are increasingly recognized in children and encompass several diseases with a monophasic or chronic relapsing course, including:

Because early diagnosis and treatment can speed recovery, reduce disability and decrease relapses, recognition of the immune pathogenesis of these disorders is important.

The strongest evidence that autoantibodies are involved in the pathogenesis of demyelinating diseases comes from the discovery of the aquaporin (AQP)-4-specific autoantibodies in NMO. Another antibody, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody, was recently recognized in CNS demyelinating diseases, especially in seronegative NMO.

In 2004, Lennon et al. (Lancet. 2004;364:2106-2112) identified NMO-IgG, a serum IgG autoantibody marker that targets the water channel AQP-4, as being 75 percent sensitive and more than 90 percent specific for NMO, implying that NMO may be a novel channelopathy.

Advertisement

As is seen in MS, time to disability in NMO is longer in children than in adults. Furthermore, children with a more benign and predominantly monophasic course are rarely positive for anti-AQP-4 antibodies. Also notable is the fact that children with a relapsing but benign course of NMO who are negative for NMO antibodies can present with high and persisting anti-MOG antibodies.

Recent studies have found high titers of anti-MOG antibodies in ADEM, AQP-4-negative NMO and recurrent optic neuritis. Anti-MOG antibodies are more frequently detected in the serum than in the CSF, and follow-up titers do not correlate with outcome.

ADEM. Elevated anti-MOG antibodies are present in up to 40 percent of children with ADEM, but clinical and neuroradiological features and treatment response are the same regardless of ADEM patients’ anti-MOG antibody status.

NMO. Some patients with clinical and neuroradiological features of NMO but who are negative for NMO-IgG antibody may present with elevated anti-MOG antibodies and respond well to therapy, which suggests this group of children may have a benign disease course.

Recurrent optic neuritis. Patients with recurrent optic neuritis are another group with high anti-MOG antibodies, whereas these antibody levels are lower in patients with clinically isolated optic neuritis and in patients with MS.

In adults, anti-MOG antibodies identify a subgroup of patients with NMO, LETM and optic neuritis that have better outcomes than those associated with anti-AQP-4 antibodies.

Advertisement

Autoantibodies, particularly anti-AQP-4, have been important in the diagnosis of NMO and serve as a monitoring tool for therapy, as NMO titers drop with successful treatment. The role of the anti-MOG antibodies found in a subset of children with ADEM, anti-AQP-4-negative NMO, recurrent optic neuritis and LETM is less clear. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical relevance of anti-MOG antibodies for the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of childhood demyelinating diseases.

Dr. Moodley is a staff physician in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Pediatric Neurosciences.

Advertisement

Advertisement

New study advances understanding of patient-defined goals

Testing options and therapies are expanding for this poorly understood sleep disorder

Real-world claims data and tissue culture studies set the stage for randomized clinical testing

Digital subtraction angiography remains central to assessment of ‘benign’ PMSAH

Cleveland Clinic neuromuscular specialist shares insights on AI in his field and beyond

Findings challenge dogma that microglia are exclusively destructive regardless of location in brain

Neurology is especially well positioned for opportunities to enhance clinical care and medical training

New review distills insights from studies over the past decade